Navigating a Rare Illness in Another Country

When my husband was 6-years-old, a tonsillectomy almost killed him.

It should have been routine, as it is for most kids. Don’t eat or drink in the 12 hours before being given anesthesia, get rounds of hugs from your family, go under, and voila! You wake up sans tonsils, ready to eat ice cream and mashed potatoes.

Except his tonsils weren’t removed that day. Instead, his jaw went rigid and his temperature shot up to 109 degrees Fahrenheit (42.7 degrees Celsius). In fact, he is extremely lucky that one of the doctors performing his surgery had seen a case like this once before, and immediately administered the only known antidote. It turns out that my husband has a rare illness called Malignant Hyperthermia or MH. It is so rare that when I tell medical professionals, I can see them mentally return to a day in medical school when it was covered as a footnote. “He’s allergic to general anesthesia,” I quickly say to avoid any embarrassment on their part. That’s usually when it clicks for them.

The thing is, you don’t know you have it until it’s an emergency. It’s passed down genetically, with a 50 percent chance that the child of someone who is MH-susceptible has it. So without a very invasive test that one can only get in a couple of places, you just assume that your children also have it.

When we had children, we knew we needed to address this. My mother-in-law had navigated the medical research in 1984, with no internet to speak of, and she had collected binders upon binders of her findings. She typically schooled anyone with whom her son came in contact on the condition, bought him a medical ID bracelet, and interacted directly with the anesthesiologists any time it was needed. I suppose with our first child’s birth we were so overwhelmed with the entire experience, plus our first real interaction with our newly registered health care, that it felt like one of those things to take care of “later.” It was put into the mental pile of things to ask our doctor at a wellness visit.

I don’t remember if I did and I don’t remember why I didn’t. I think now that I always supposed my husband or myself would be around to tell a medical provider. With anything as extreme as needing anesthesia, surely one of us would be nearby? How foolish. This is one situation when considering the worst-case scenario would have been the best course of action.

Once we had two children and were moving to a different country, it occurred to me that even if we were present, how could I make sure a doctor knew what I was saying, if English is their second language? My husband would also be on a worksite, which meant his risk for harm felt more elevated than in an office. He would also need more protection on hand than just my name and number as his emergency contact.

It took me a while to figure out exactly what I needed to do for our full due diligence.

Get a clear translation of the illness

I asked a translator from Vista Clinic to discuss it with her two colleagues, one who spoke English as his first language and another doctor who spoke Mandarin as her's. I was texting with them and my mother-in-law to learn the clearest way to state what MH is and what not to do. A translation is not always word-for-word, so I wanted to be sure any translation was very clear. Ideally, you can also put what to do in case they have an attack, but that could not fit. Because it all needed to be legible in English and Mandarin so we could do the next step.

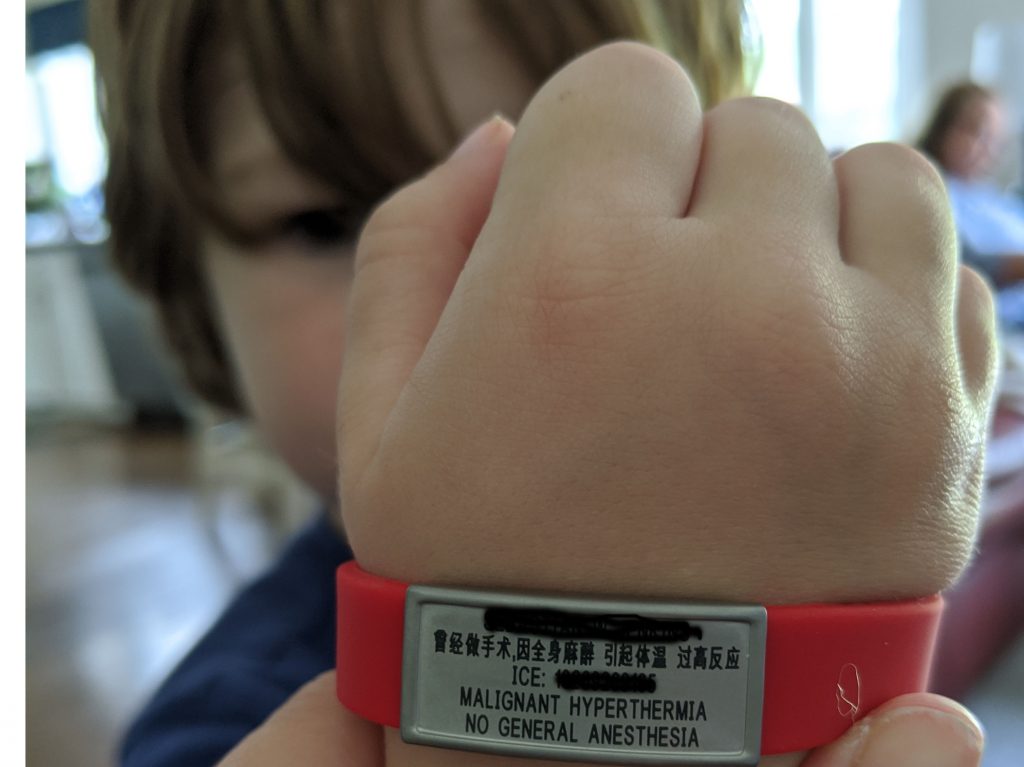

Get a bilingual medical ID bracelet

This took me the longest to find. I had the jewelry but couldn’t get an engraver who could do both. I found referrals but all leads were dead ends. Finally, I asked in an expat group online and I found the company ROAD ID, who will engrave in both the Latin alphabet and Chinese characters.

Get them into the habit of wearing their bracelets

This was easier than expected. Lucky for me, they like jewelry. I showed them their Daddy’s, explained what MH is, then made it clear they need to wear this bracelet all the time, every day. Since we got the bilingual ones during quarantine, it became part of our new routine: shoes, masks, medical bracelets. They always return to the same basket in our home and for the most part, we’ve never permanently lost one.

Write and translate a letter. Make multiple copies

I’m still in this process. Again, I turned to a group of expats who travel frequently and asked if there was anything else I should do. People popped into the comments with extraordinary stories ranging from what they did for MH, how they navigate a fatal nut allergy around the world, and more. The main conclusion I came out with is that I need a letter explaining exactly what MH is, what causes it, and how to treat it. Then I should return to the same medical professionals who translated for the ID bracelet and have them translate it. After that, I personally hand a copy of both letters to every grown-up who will ever have my children under their care: teachers, nurses, principals, art teachers, coaches, ayis. I know people who always have it translated into the native language of wherever they travel as well, and they have, in fact, needed to use it.

Where will school/work take them in case of emergency? Do they have the remedy to this illness on hand

This is the trickiest part. I did contact the hospital where their school would take them, and no, they do not have dantrolene on hand. However, we may have miscommunicated, because they asked the pharmacy, and that isn’t where I think the ER would go to find the main remedy to an MH attack. So I am trying to find the correct person who can answer my question and/or how to carry dantrolene myself if possible.

Teach your child to advocate for themselves and siblings, if applicable

I am always proud when a babysitter says my youngest lost his bracelet and immediately told her about it, or when a teacher tells me that my son already explained it to them. They need to be their own medical advocates. It is a habit that will help them throughout their lives. They know how to say “I can’t have anesthesia” clearly in English, and the next step is to teach them the Mandarin phrase.

Bottom line is: Don’t put it off

I was purposefully naive at the thought that we would need to address this proactively, even when reminded. It never felt urgent until I was uncomfortable with my ability to communicate a rare medical condition in a foreign tongue. Plus, who knows what my mental state would be if my children were hurt?

No parent wants to consider what would happen if they are not present, or worse, unconscious when their child needs to go to the hospital for a medical emergency. But we need to. With a rare illness, or something like a nut allergy that is so common in many areas of the world but extremely rare in others, parents and guardians must be proactive, we must be ahead of any emergency, and in all necessary languages. That is the only way to retain any peace of mind.

READ: Furry Situations: Important Rules Regarding Pet Ownership in the Capital

This article originally appeared on our sister site, beijingkids

Images: Pexels, Cindy Marie Jenkins

Related stories :

Comments

New comments are displayed first.Comments

![]() Sikaote

Submitted by Guest on Thu, 10/01/2020 - 09:34 Permalink

Sikaote

Submitted by Guest on Thu, 10/01/2020 - 09:34 Permalink

Re: Navigating a Rare Illness in Another Country

Write and translate a letter.

Also a last will and testament.

Validate your mobile phone number to post comments.