Tracing Heated Roots: How the Beloved Chili Arrived in China

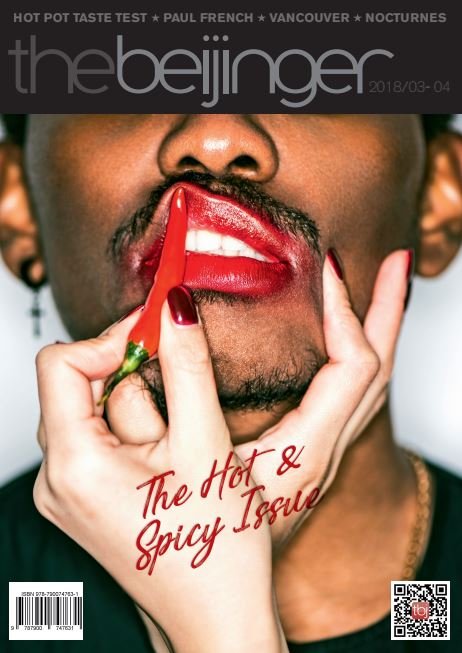

Now that you've acquired a taste for all things fiery thanks to the Beijinger's recent inaugural Hot & Spicy Fest, be sure to check out our ongoing chili related restaurant coverage and the latest issue of our Hot & Spicy themed magazine so that you can maintain the tantilizing burn. Speaking of our magazine, here is a feature from that spicy issue about the history of chilis in China.

I was eating hot pot with a group of Chinese friends recently. As is my custom, I ordered the spiciest oiliest hell broth on the menu, a fiendish concoction of (I’m-sure-it-wasn’t) gutter oil, Sichuan peppercorns, and, of course, a veritable red slush of chili peppers. I was soon sweating like a poodle humping Chris Farley in a woodstove and releasing noxious gas so horrific that it may have violated the Geneva Protocol. It was awesome.

The domesticated chili pepper, Capsicum annuum: It is about the pleasure of pain, a masochistic rush of released endorphins and sweaty upper lips. It is nearly impossible to imagine Sichuan Cuisine (or Indian or Thai) without the humble chili, and yet until 500 years ago, the chili was unknown to chefs in this part of the world.

This venerable spice, the devil’s own, was part of a great global shifting of crops, animals, people (and disease) known as the Columbian Exchange. Starting in the 15th and 16th century, conquerors and explorers from Western Europe took chili peppers, papayas, peanuts, tobacco, tomatoes, corn, and hundreds of other species from the Americas and introduced them to the trade routes of Asia.

Meanwhile, apples, coffee, citrus fruits, onions, cattle, pigs, and horses made the trip in the other direction.

At the same time, millions of people – many against their will – also traveled between the continents taking their culinary culture and favorite ingredients with them from one part of the globe to the other.

Enter the chili.

I’ve had knock-down arguments with fellow capsaicin connoisseurs on the provenance of our preferred pepper. When I tell my dining companions that their mighty chili is not native – is, in fact, like me a foreigner to their shores – they look at me as if wondering, is it possible that this Lao Wai is intentionally hurting the feelings of 1.3 billion people?

Chili peppers have been part of the culinary culture of the Americas for almost 10,000 years. According to a study published by the National Academy of Sciences in 2014, the earliest evidence of domestication occurred nearly 5,000 years ago in what is today Mexico.

Spanish and Portuguese explorers to the Caribbean basin encountered chilies, which they identified with the black pepper, a separate plant species, because of its spicy palate. They brought samples back to Europe, first as ornamental plants and then for adding a little extra kick to their food and an Old World culinary revolution was underway.

Once chilies started appearing in the markets and bazaars of the Indian Ocean trading ports, their use spread rapidly throughout South Asia and into China, Korea, and Japan.

According to an article published in 2005 by two Chinese researchers in the journal the Agricultural History of China, the first record of chilies in the Middle Kingdom is from a 1671 gazetteer in Zhejiang province: “It is red and can be used for seasoning.” There is another reference in 1682 from Liaoning, the coastal orientation of these early chili adopters providing some evidence for the chilies’ arrival by sea. The pepper-popping people of Hunan – Mao was reportedly a capsaicin devotee – record that chilies appeared in their province in 1684.

Surprisingly, the first reference in a Sichuan isn’t until 1749 although given the trauma Sichuan endured in the 17th century (the province suffered a severe population decline because of wars and rebellions during that period) the relatively late record might not be the best indicator of when the chili arrived in Chongqing.

Why did some parts of China adopt and adapt chilies while others gave the pepper a hard pass? Notably, Guangdong and Zhejiang, despite being two places chilies arrived first in China, eschew spice in their cuisine. And yet in Hunan and Sichuan – the two spice rivals – chilies are more than just a source of heat in the meat but are an integral part of local culture and lingo.

Both share the la meizi and hong lajiao archetypes of women who know a couple of different ways to turn up the heat. Both have cities notorious for damp weather where nothing wards off the baleful influence of cooling than a little hot spice in the soup.

But whether it’s about the women or the weather, the chili has become a staple of some of China’s most famous regional cuisines. After 500 years of nuking otherwise boring vegetables and semi-palatable animal parts, who cares where the chili originated, it’s most likely here to stay.

Photos: Courtesy of BEC-Tero, Faradeed, MC-Sichuanhot