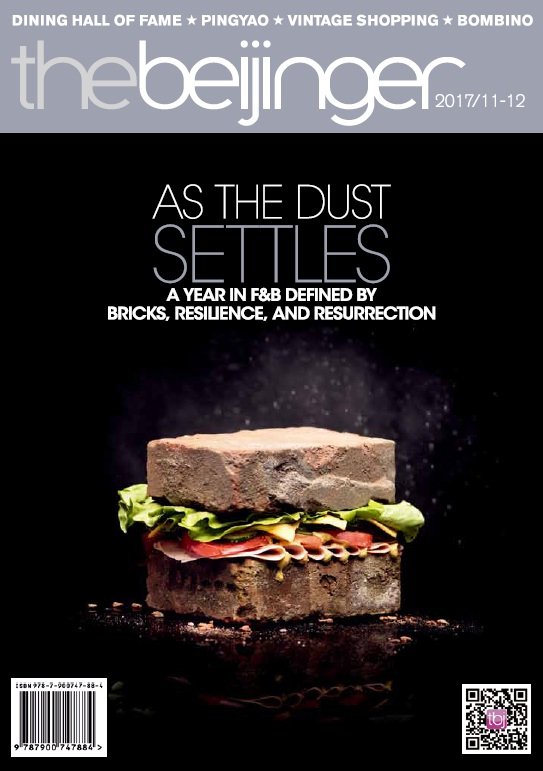

Bricked-Up, Bygone Hutongs: Those That Benefited From, and Were Slighted By, the Chai-ing of 2017

Though the wall had gone up to cease their rowdiness, Rain and Xiaoshuai refused to be silenced. Yes, the renovations of Fangjia Hutong have long since pushed the respective owners of Cellar Door and El Nido out, turning the once vibrant party alley into a barren byway. But they're both unafraid to speak about, and against, what they deem to be business-busting, culture-slaying bricklaying.

The pair returned to the now all but empty hutong for a photo shoot and interview in October, a few months after the chai-ing forced them out. Rain said: “Maybe the authorities think it is good for themselves to not to have to manage too much, and to get more tax revenue by making Beijing like a standard international city. But the way they manage the problem is quite brainless and careless.” She feels that the citywide street-level renovations only benefit prosperous Beijingers. “They just smash down little businesses by using some excuses which they themselves know are all lies. Soon the rich, good, proper Chinese people can just do everything in the big shopping malls.”

Rain had spent much of this past summer struggling to keep her bar Cellar Door open despite both intensifying complaints of the local residents living nearby, colloquially referred to as “the neighbors,” and renovations that partially blocked her business’ doorway, leaving only a small gap through which to peer inside. She cheekily set up a ladder outside for patrons to climb onto and place their orders, renaming the place Cellar Window, but business slowed. In mid-September, she and her neighboring bar and restaurant owners were finally ordered to vacate.

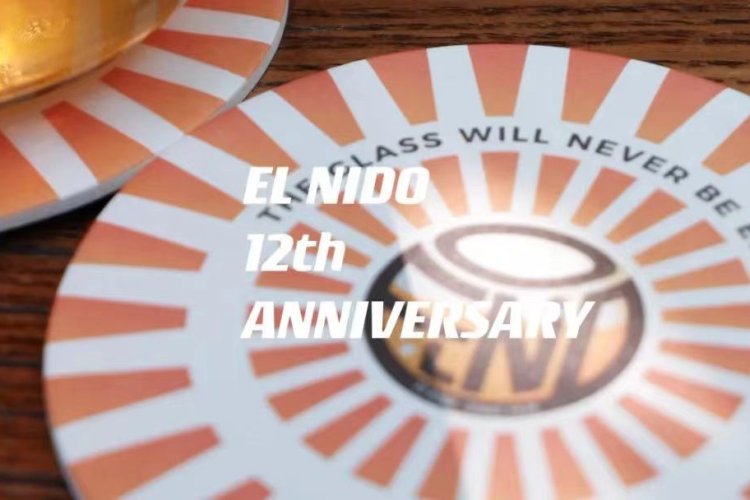

Xiaoshuai, her neighbor and owner of one of the alley’s longest-running bars, El Nido, accompanied Rain for the interview and photo shoot. Despite having lost El Nido after owning and operating it for years, Xiaoshuai and his business partner Zak Elmasri have relocated their Fangjia Hutong cocktail bar Fang south to Jiaodoukou, and he tries to remain optimistic.

“The hutongs are colder and colder,” Xiaoshuai said, clearly not referring to the weather. “There’s hardly anything here in Fangjia anymore, except for the public toilets! Many interesting businesses are gone. But it’s a process. I can’t recover what we had, but maybe we can keep going and maybe eventually it will be better. After all, I’m still living in the hutongs, and am determined to stay.”

The same can’t be said for many other former street-level business owners like Rain, who plans to move to the UK with her family. Nor for Ross Harris, who relocated to Cambodia after his Beixinqiao Toutiao cocktail bar Más was shuttered. Before his departure, he recalls “arguing with a construction crew trying to keep the front from being bricked for at least a few more nights. I pleaded and got just enough time for a cathartic final few closing parties.”

Such bittersweet farewells for Ross and his Más cohorts were fleeting, however, especially as construction on Beixinqiao Toutiao began in earnest. He was especially galled by how laborers sledgehammered and destroyed the bar’s bathroom, despite his pleas, in what amounted to “a vicious free-for-all with no recourse. If you were licensed and paid taxes like we did, or operated in a DIY way, it was irrelevant in the end.”

Though such refrains reverberated throughout the hutongs in 2017, several streetside businesses in Sanlitun and other neighborhoods met similar fates. Claudia Masüger, CEO of Cheers Wines, recalls how Sanlitun North was one of the first haunts to be hit by bricklaying this past April. Though she has many other branches of her wine shops around town, she says that one was special because “it was the store which made us famous within the Sanlitun area. It was the place to meet friends and have a drink before partying in Sanlitun, a kind of foreplay in the city.” She adds that the bricking up of the area is a “heartbreaking memory.”

Not everyone was sad to see such businesses gone, especially on that ground-level Sanlitun strip once occupied by Cheers, the Turkish Doner, and several shops. The Beijing Radio 774 FM Lifestyle program, for instance, conducted touching interviews with everyday tenants living in apartments above ground-floor businesses, some of whom contended with backed up plumbing because the unlicensed restaurant below didn’t have its pipes up to code, while others dealt with so much noise from neighboring businesses that their children had trouble studying for the gaokao and other crucial exams.

While such sentiments may not have occurred to (and might give pause to) much of the throngs of foreigners who frequented streetside businesses, little of it comes as a surprise to Michael Meyer. After all, the travel and history writer began researching such relentless hutong redevelopment more than a decade ago for his 2009 book The Last Days of Old Beijing, a project that helped him realize the redevelopment’s “pattern has remained unchanged since the early ‘90s, when Beijing's modern makeover began: a lack of transparency and no debate in public forums or in the media about the shape the city is taking. What's different this time around is the targeting of businesses which, by and large, were started by migrants to the city. The hutongs have always excelled at making more Beijingers; migrants start businesses, settle, and buy into the status quo. But officials have long wanted migrants out of central Beijing.”

Meyer goes on to concede that “Beijingers often feel like tenants in their own city, unable to shape the place to their community's needs. No one should have to live above a noisy bar, but as other global capitals have proven, there are ways to assimilate residences with nightlife without tearing down either.”

Many business owners, like Harris, can sympathize in that regard. However, he’s quick to point out: “the most affected by demolitions near Más were residents, not businesses. Our neighbors lost their front door and kitchen. It happened quickly and spiraled into almost a bloodlust, with piles of rubble in every alley.”

That’s the kind of nuanced take that hutong historian Zhang Jinqi has spent much of his career on. The Dashilan resident and author of numerous books about those famed Beijing courtyards and alleyways says that everyday hutong dwellers will, if they don’t already, grow to miss the small shops, restaurants, and other facets of street life that have been razed along with noisy bars and careless eateries that back up the plumbing of nearby apartments, and other businesses that they’d rather see gone.

READ: Hutong Development and the Businesses Rising Again From Beijing’s Brick Dust

For Zhang, chai-ing and wall-building are only superficial measures that in no way address the true issues plaguing Beijing streetside proprietors and dwellers – incoherent property laws, population density, and concentration of resources and economic opportunity. Zhang wishes the authorities would focus on all that, rather than chai-ing neighborhood noodles shops and hipster expat bars. “Urban ecology must be naturally born, and it should be like an ecosystem. You can’t just rely on executive orders, like a grand knife that comes down from on high to carve the solutions out.”

Instead, Zhang – like so many other Beijingers that prefer vibrant streets to glossy shopping centers – says he would at least like to see “more houses and properties in the hutongs of Beijing classified as heritage areas. Yes, of course, it's harder to protect history than to build something new. But I feel that the UK, France, Italy, and other countries have done well to solve these problems. Although China has many differences from them, I still think we can do it, too.”

This article first appeared in the Nov/Dec 2017 issue of the Beijinger.

Read the issue via Issuu online here, or access it as a PDF here.

More stories by this author here.

Email: kylemullin@truerun.com

Twitter: @MulKyle

Instagram: mullin.kyle

Photos: Uni You