Weekend Walk: The Basics of the Forbidden City

Weekend Walk is your guide to getting away in the city using nothing but your own two feet.

For over 600 years, the high vermillion walls of Beijing’s Forbidden City hid the secrets of 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties. Built between 1406 and 1420, the Forbidden City took over one million laborers and approximately 100,000 architects, engineers, artisans, and craft people to complete.

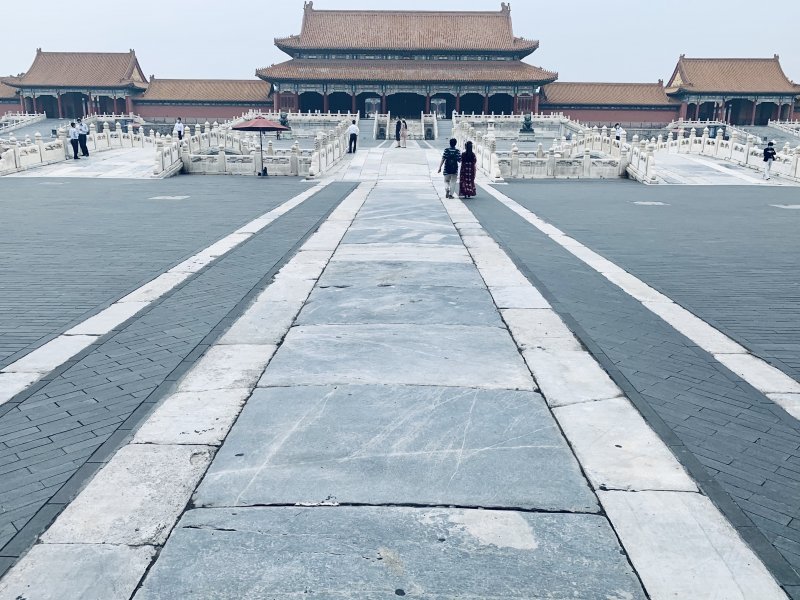

This walk is the simplest and most straightforward way to see the Forbidden City, proceeding from the Meridian Gate in the front, down the main central axis, and exiting at the northern end of the palace across the street from Jingshan Park. Most people (too many people?) take this route, but it’s only a starting point for exploring this massive palace.

The Palace Museum renovates and opens new sections of the former imperial residence for public viewing each year. It is worth getting lost in the courtyards, galleries, and gardens east and west of this central route for a different – and often less crowded and more interesting – side of the Forbidden City.

For an in-depth exploration of the palace, full of stories, details, and history beyond the basics of this post, be sure to check out these excellent Forbidden City walks and tours offered by Beijing by Foot, Beijing Postcards, and the Courtyard Institute.

Meridian Gate & the First Courtyard

Pass through the security checkpoint and take a moment to appreciate 午门 Wǔmén, the main entrance to the Forbidden City. Wumen means Meridian Gate, and with good reason. Turn around for a moment and look south, back toward Tian'anmen. Can you see how the gates of the palace line up? This sequence of gates follows the Central Axis of Beijing, which runs through the heart of the city from Yongding Gate, in what was once the southernmost city wall, to the Drum and Bell Towers, which kept the time in the imperial city. Today, this imaginary line extends even further north to form the central axis of another monument: the Olympic Green.

Running through the first courtyard is the “River of Golden Water.” Practically, it is good to have water flowing in the Palace for drainage and fire control at the same time. Water in the front balancing a hill (Jingshan) in the back also makes for pretty good 风水 fēngshuǐ.

Gate of Supreme Harmony (太和门 Tàihémén) & Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿 Tàihédiàn)

Across the bridges is the Gate of Supreme Harmony, the entrance to the main ceremonial space of the Forbidden City, the large courtyard in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony.

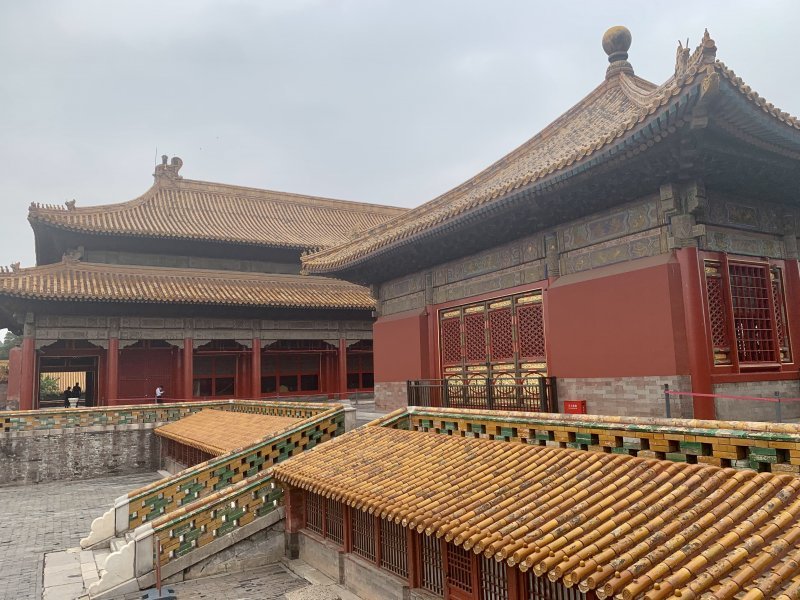

At over 35 meters in height, the Hall of Supreme Harmony is the largest building in the Forbidden City. Similar to most of the buildings in the Palace, it has porcelain tiles glazed in the imperial color yellow. The hall was used for significant events and ceremonies, including coronations, distinguished visits, imperial weddings, and festivals and holidays.

While sometimes referred to as the throne room – and there is a throne sitting forlornly inside – routine matters of state and court meetings generally occurred in other parts of the palace. In the Ming dynasty, the location for these events was the Gate of Supreme Harmony. In the Qing era, those meetings moved to the Gate of Heavenly Purity, where the “Outer Court” gives way to the “Inner Realm.”

You’ll notice some large bronze vats on either side of the hall (and others strategically located around the Forbidden City). These are part of the fire control system for the Palace. In the days of the emperor, the Forbidden City used to catch on fire with shocking regularity.

An earlier incarnation of the Hall of Supreme Harmony burned down soon after the palace opened for business in 1421. Fires were a continuous fear of those who lived in the palace. The iron and bronze vats were always filled with water to put fires out in one of the nearby buildings should they arise. In the winter, hot coals and logs were placed under each of the bronze vats to keep the water from freezing.

Hall of Middle Harmony (中和殿 Zhōnghédiàn) & Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿 Bǎohédiàn)

Behind the Hall of Supreme Harmony sits a smaller, square building known as the Hall of Middle Harmony. This was used primarily as a ready room and preparation space for the emperor before attending major events in the Hall of Supreme Harmony. The emperor would also prepare for significant state rituals here.

After the Hall of Middle Harmony, the next hall is the Hall of Preserving Harmony. This space was a kind of multi-function room for the Palace. Several types of events took place here, such as government and wedding banquets and the final rounds of the imperial examinations.

In terms of architecture, the Hall of Preserving Harmony looks very similar to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, but there are some subtle differences. Look up at the eaves. Can you find the series of small mythological beasts in a procession? You can see that the eaves on all of the buildings and gates around you have their collections of fantastic beasts. The difference is how many adorn each set of eaves.

The first in the procession seems a little bit like a man riding a chicken, with most sources describing the figure as “an immortal riding on the back of a phoenix.” The last figure resembles a dragon with two large horns and a flowing mane. This figure is also found on most buildings in the Forbidden City.

Between this dragon figure and our phoenix rider is a procession of nine small “walking creatures.” Nine is a number with a lot of cosmologic juice in Chinese architecture, and it is the usual maximum for mythological roof decorations. But look back at the Hall of Supreme Harmony. If you count the number of mythical beasties on its eaves, you’ll see there are ten.

The additional figure represents the supremacy of this building over all the others in the Palace. (For further context, you can refer to the above scene from the mockumentary This is Spinal Tap.)

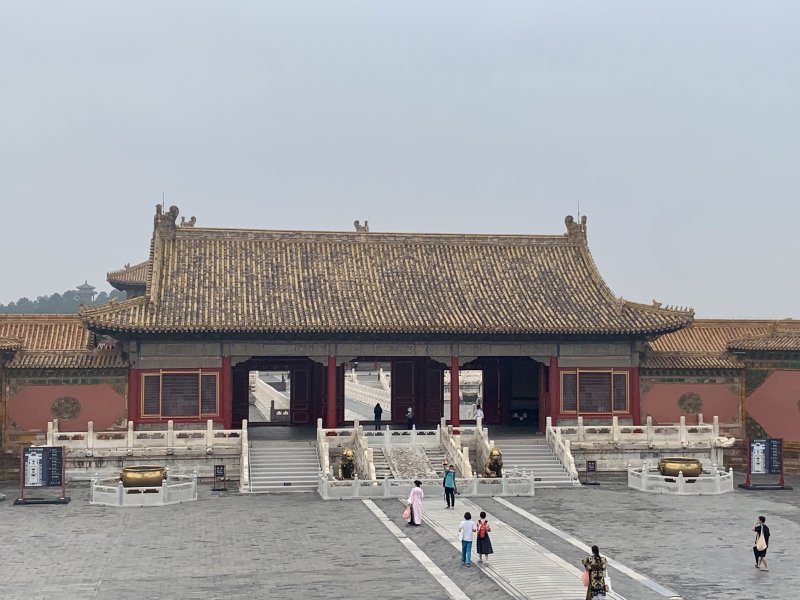

Gate of Heavenly Purity (乾清门 Qiánqīngmén)

As you descend to the courtyard behind the Hall of Preserving Harmony, you’ve reached one of the most important spots in Qing China: the Gate of Heavenly Purity, which was one of the portals between the “Outer Court” of the Forbidden City and the “Inner Realm.”

The emperors of the Qing dynasty often held court here, meeting officials, reading documents, and making the day-to day-decisions required to run an empire. The Grand Council 军机处 Jūnjīchù, who served as advisors to the later Qing emperor on policy matters and were privy to the most sensitive documents, worked out of the low building to the left of the Gate of Heavenly Purity. The building to the right of the gate, opposite the former Office of the Grand Council, was once a Starbucks. Seriously.

Palace of Heavenly Purity (乾清宫 Qiánqīnggōng)

Initially the royal residence, the Palace of Heavenly Purity was the place where 14 Ming emperors and the first two Qing emperors lived and worked. It was also the site of a fair bit of palace drama.

According to one tale, the Jiajing Emperor, who ruled the Ming dynasty from 1521-1567, had a rather unpleasant fright when a conspiracy of concubines nearly assassinated him. A large tablet is hanging from the ceiling inside the Hall that reminded emperors to be “Righteous, Forthright, and Honest.”

Behind that tablet, the Yongzheng Emperor placed an “Heir Apparent” box that contained the name of the next emperor. The irony, of course, is that the Yongzheng Emperor came to power amidst a cloud of suspicion that he was not his father’s preferred choice as successor.

Hall of Union and Peace (交泰殿 Jiāotàidiàn) & Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤宁宫 Kūnnínggōng)

Like the Hall of Middle Harmony, the Hall of Union and Peace was used as an antechamber and preparation space for rituals. Located behind the Hall of Heavenly Purity, this smaller palace corresponds to the Hall of Middle Harmony in the Outer Court.

In this case, the empress, not the emperor, was its primary beneficiary. The empress was responsible for her own traditions, including the annual sacrifices to the God of Silkworms. She prepared for her role in yearly rituals in the Hall of Union and Peace.

Behind the Hall of Union and Peace, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility had a variety of functions for the imperial family. The Qing practiced daily rituals dating back to before they conquered China.

These rituals were part of the Manchu’s original religious beliefs, a form of animism and worship of spirits in nature. The Palace of Earthly Tranquility was also used as a bridal and honeymoon chamber for the emperor and his new wife.

Imperial Garden (御花园 Yùhuāyuán)

The flowing and whimsical design of the back gardens offers a welcome break from the rigid symmetry of the Forbidden City. It is filled with rockeries, centuries-old trees, shrines, and temples with pathways inlaid with mosaics.

While the garden is lovely, it was more of a convenient substitute for when the imperial court could not escape to the manicured landscapes and lavish palaces built by the Qing emperors at Yuanmingyuan and the surrounding gardens outside the city walls.

Gate of Divine Might (神武门 Shénwǔmén)

The Gate of Divine Might is one of only two exits from the Forbidden City open to the public. (The Meridian Gate, where we started the walk, is the only entrance). From here, you can cross under the street and continue your exploration by entering Jingshan Park and climbing the steps to the top of the hill for a 360-degree view of historic Beijing, including the Forbidden City.

About the Author

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, organizing history education programs and walking tours of the city, including deeper dives into the route and sites described here.

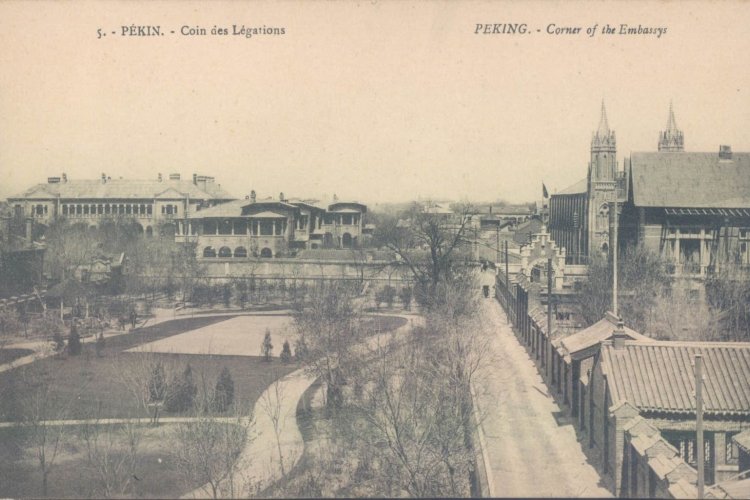

READ: Weekend Walk: Holy Peking! Or, Walking Where Foreign and Chinese Once Collided

Images: Jeremiah Jenne