We Built This City: A Look at Four Beijing City Planners From Empire to Modern Capital

Who are the famous figures who left their mark on Beijing’s urban landscape? Is there a Beijing equivalent of Pierre Charles L’Enfant and his design for Washington, DC, or Lúcio Costa and Brasilia? What about a Baron Haussmann, who famously (some would say notoriously) renovated Paris under Napoleon III?

The list of people who played a role in building Beijing could fill volumes, never mind the countless people whose labor was essential to the city's evolution but whose names sadly have gone unrecorded. Here are just a few of the people whose legacy lives on in the streets, structures, and the cityscape of Modern Beijing.

Kublai Khan [r. 1260-1294]

There had been cities where Beijing is today dating back thousands of years, but very few structures remain from the days before the Mongol emperor decided to shift his primary capital from Shangdu out on the steppe to be a little closer to his new Chinese subjects.

As befits the heir to an empire that stretched from Korea to Kyiv (although he annoyingly had to split up his inheritance among a bevy of family members and rival khans), Kublai could still take advantage of the best architects and minds from throughout Asia.

Liu Bingzhong (1216-1274) had been an official in the Jin Dynasty, vanquished by Kublai’s grandfather Genghis Khan. Kublai Khan heard that Liu was a man of great ability (and possibly also possessing powers of foresight and fortune-telling) and invited Liu to join his court as an adviser. Liu Bingzhong would go on to design the Khan’s original capital at Shangdu and to plan the renovation of the Khan’s new digs in present-day Beijing.

Amir al-Din (d. 1312), a Muslim architect and engineer from Western Asia, assisted Liu Binzhong in the building efforts while a talented mathematical and engineering prodigy from Xingtai in Hebei named Guo Shoujing (1213-1316), oversaw the building of the canals, waterways, reservoirs, and lakes which still flow through Beijing today.

The Yongle Emperor [r. 1402-1424]

The father of the Yongle Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-1398), was one of the generals who led a rebellion that overthrew the descendants of Kublai and kicked the khans to the curb (or at least back into the steppe). Zhu Yuanzhang then founded the Ming Dynasty and asked one of his most talented officials, Liu Bowen (1311-1375), to renovate the khan’s old capital in present-day Beijing into something a little more Ming-appropriate.

After Zhu Yuanzhang’s death and a minor family squabble involving massive armies and thousands of casualties, the future Yongle Emperor defeated a nephew, sacked dad’s old capital in Nanjing, and prepared to shift his primary base of operations to the north. Between 1406 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor employed over one million workers and 100,000 architects and artisans to build the Forbidden City, an early incarnation of the Temple of Heaven, and the city’s modern walls and gates.

Later Ming emperors would add walls (including the southern walls, which would become the “Outer City” in the 16th century, reinforce gates, and renovate some of these sites, but the layout and legacy of Yongle’s capital remain in the streets and landmarks of Dongcheng and Xicheng today. It’s pretty amazing what you can build if you’re completely ruthless and have access to a nearly endless supply of cheap non-union labor, just like the Yongle Emperor. Or Jeff Bezos.

The Qianlong Emperor [r. 1736-1796]

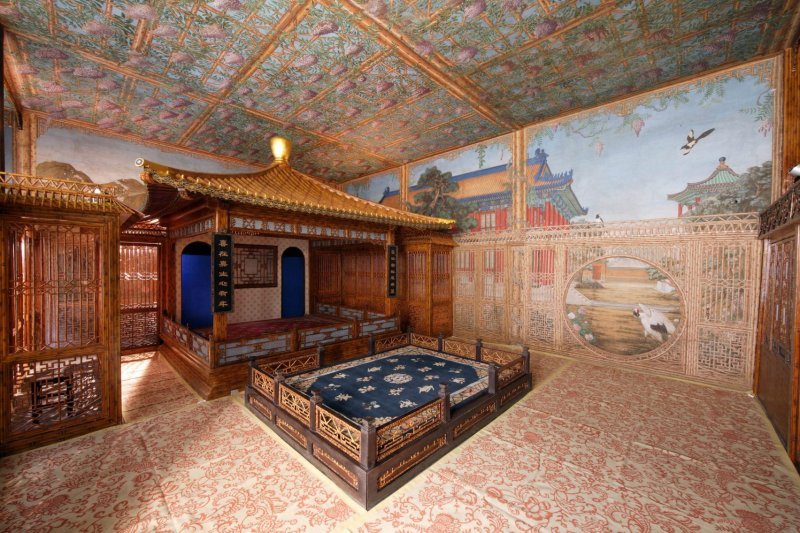

If Kublai Khan and the Yongle Emperor get credit for the foundations of modern Beijing, we should tip our peacock-feathered caps to the Qianlong Emperor for transforming the city’s most famous imperial structures into the tourist attractions we know today.

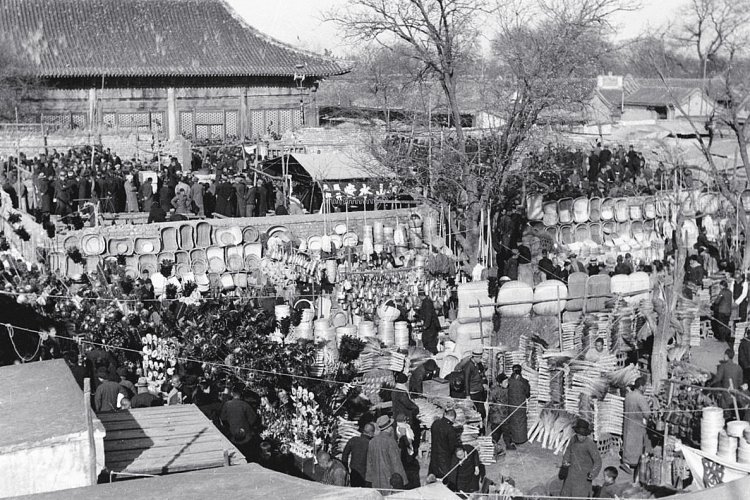

Many sites, including the Summer Palaces, the Temple of Heaven, imperial parks such as Beihai and Jingshan, and even large sections of the Forbidden City looked very differently before Qianlong began a series of massive — and expensive — renovation projects in the 18th century. Do you know those people on TV shows who compulsively flip houses and use highly punchable terms like “good bones” and “curb appeal”? Yeah, that was the Qianlong Emperor.

When he wasn’t expanding his empire, launching military campaigns against rival states, and pwning King George III, the Qianlong Emperor kept busy updating his capital, rebuilding palaces and temples, expanding parks and gardens, and emptying the imperial coffers. It’s little wonder that so many Beijing sites have historic markers that read, “First built in [pick your early dynasty], but completely renovated and rebuilt by the Qianlong Emperor in the 18th century…”

Zhou Enlai (1898-1976)

A certain portly chairman gets much of the blame, but it was premier Zhou Enlai who oversaw the transformation of Beijing from a former imperial city into a socialist capital.

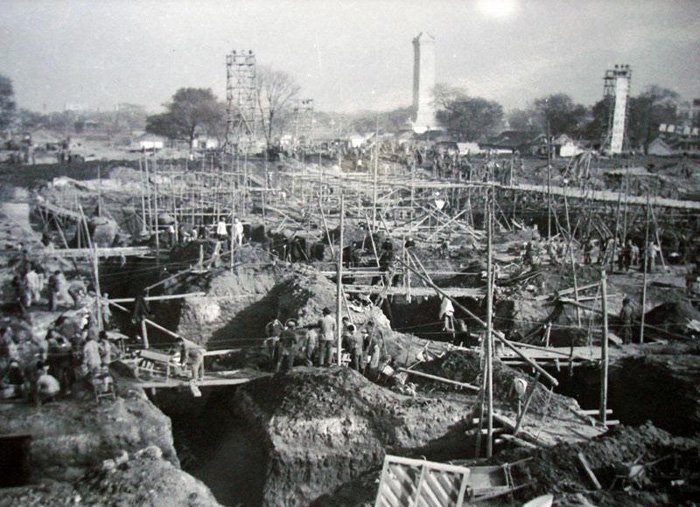

Many architects submitted plans, and a proposal from the famous urban planner Liang Sicheng (1901-1972) that would have saved the historic core of the city and the capital’s walls and gates was among those rejected. Instead, beginning in the 1950s, roads were widened and paved, many of the remaining walls and gates were demolished, and a series of grand structures were built along a new axis, this one running east to west in revolutionary defiance of the north-south Central Axis that had been a feature of Beijing dating back to the days of Liu Bingzhong and Kublai Khan.

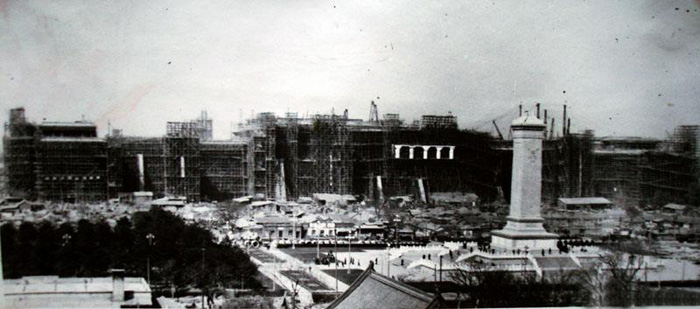

Ten Great Buildings based on Soviet architecture but incorporating a few Chinese elements, including the Great Hall of the People, the structure housing the China Revolutionary History Museum and the National Museum of Chinese History (now combined as the National Museum of China), the Minzu Hotel, and many of the most important ministries lined the expanded and widened Chang’an Boulevard.

A team of architects worked under the supervision of Zhou Enlai and the State Council. Zhang Bo (1911-1999) and Zhang Kaiji (1912-2006) studied architecture at the same university in Nanjing during the Republican era. Zhang Bo helped design, among other landmarks, the Great Hall of the People and the Cultural Palace of Nationalities on Chang’an Boulevard. Zhang Kaiji, who shared a surname although not related to his fellow architect, was responsible for designing the museum space across the newly expanded plaza which became Tiananmen Square.

About the Author

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot and organizes history education programs and walking tours of the city

Sources and Further Reading:

Chang, Yung Ho. “13. Zhang vs. Zhang: Symmetry and Split: A Development in Chinese Architecture of the 1950s and 1960s”. Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-Arts, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2011, pp. 301-312.

Kong, Haili, Li, Lillian M., Dray-Novey, Alison J. Beijing: From Imperial Capital to Olympic City, United States: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

READ: Story of the 'Jing: The Legacy of the Jesuits in Beijing

Images: Wikicommons, Jeremiah Jenne, dazeen.com, 赵庆伟