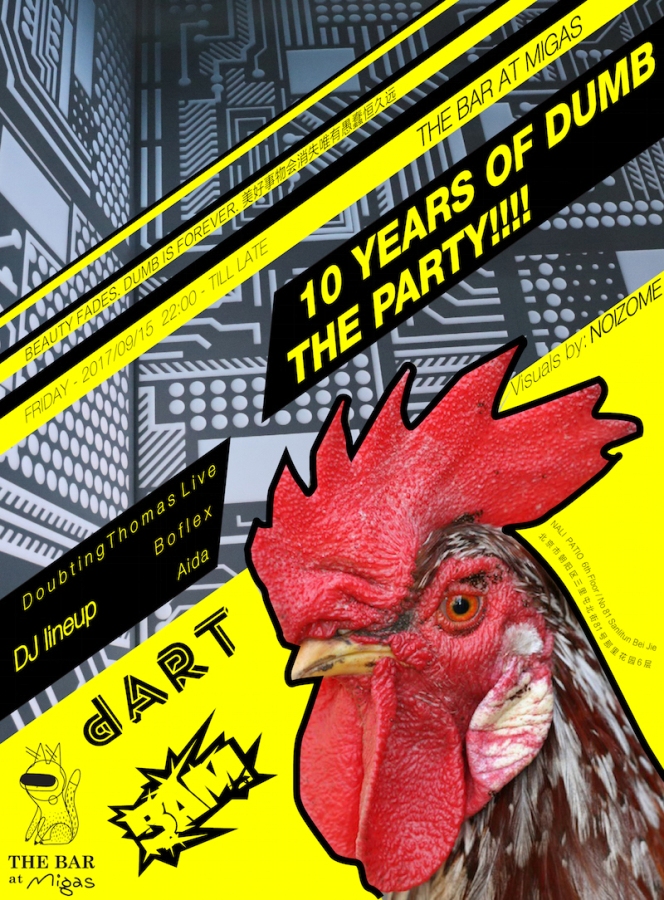

Playing it Dumb: A Talk With BAM Architects Ahead of Their 10 Year Anniversary With dART

Ballistic Architecture Machine (BAM) have been heading conceptually driven reimaginings of public spaces, buildings, and art installations since their settling into Beijing back in 2009. Now, they're joining forces once again with Miao Wong's dART collective for a decidedly more humble celebration of all things Dumb.

The two initially collaborated at the inaugural dART party in 2015, whereby BAM was contracted to design the 3D mapping visuals that would become the stage's backdrop, but not all of their projects would come to such successful fruition, which is where this retrospective of failure comes about. These forays into failure include last year's Pheonix Burn, which was slated to become Beijing's answer to Burning Man (minus the Silicon Valley bros and the unending desert drug use), as well as the time dART put on a pay-what-you-want show by German dance duo FJAAK and "getting only RMB 2,000, which hardly covered even the cost of the well-designed box itself."

As for BAM, as the dART press materials put it, "Over the past 10 years, BAM’s admittedly dumb strategy of ‘just say yes’ has led to countless mistakes yet ultimately resulted in a portfolio of strange and exuberant works with a seemingly incomprehensible breadth; from the design of costumes, parades, building facades, parks, furniture, wickless hand candles to musical events."

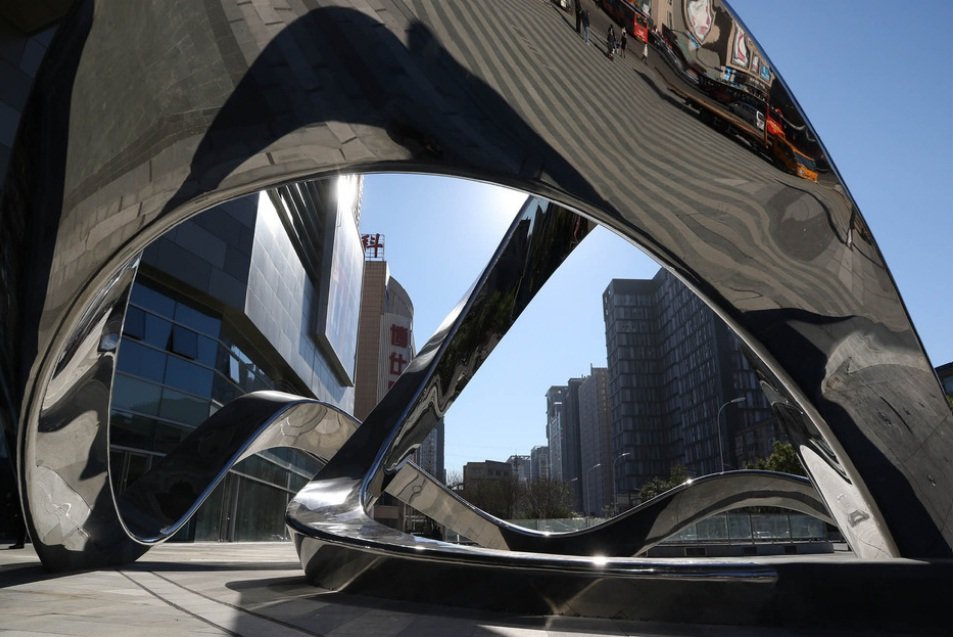

That strategy, however, has also led to a number of successes, including architectural jobs throughout China such as a mirrored Möbius strip-like sculpture in Shenyang, a shimmering facade in Chongqing, and a playground behind Beijing's Indigo Mall (plus a shanzhai version for good measure).

You can see a selection of BAM's work at the Tabula Rasa Gallery until September 15, at which point the exhibition closes and the fun moves to Migas for their joint celebration with dART. Boflex and Aida will take the decks, followed by a live set from Doubting Thomas. Noizome will provide visuals.

Below, we had a chance to chat with the BAM team about how it all began, the differences between doing what they do here and in the States, as well as the changes that Beijing's city center is currently facing.

You got your start as a three-person design team in Massachusetts, US in 2007, and you now have an office in New York. How did the creation of an office in Beijing in 2009 come about? Was it a conscious move on your part or were you contracted for a job and ended up sticking around?

Only after practicing in Beijing for a couple years did we then establish ourselves in New York with a small studio. For all intents and purposes, our main and head office is in Beijing. We are not a New York company coming to Beijing. We are a Beijing company going to New York. Our ‘base’ is absolutely Beijing.

Coming to Beijing was a choice. After completing our first project in Taipei, we had decided that we were going to move to China. At that point, it wasn’t necessarily clear where we were going to land. We looked at Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, as well as other Southeast Asian cities such as Bangkok. However, Beijing just clicked for us in a few different ways. Given that we were moving from the West, the idea of leaving a western city for a westernized city wasn’t very attractive. Our logic was if we moved to Shanghai, or Hong Kong, why bother moving to China at all. I think initially we wanted a more authentic experience, and while cities like Shanghai and Hong Kong are very nice, and do have an inherent ‘Chinese-ness’ we were looking for to provide ourselves with a greater contrast.

Additionally, Shanghai is a better place for business than Beijing. Shanghai is more convenient, easier, better climate, one could argue it's ‘better’ in almost every way, and this attracts more foreign business. We did not want to be perceived as westerners coming to China to make a buck, we didn’t want to establish ourselves alongside a whole host of service oriented foreign design firms who are in China for the economy and not for the culture. BAM is not in China 'for the money,' BAM is in China to advocate for the urban landscape as a cultural medium. Conceptually, Beijing is the only true choice in this respect.

By extension, since Shanghai is certainly ‘easier living’ from a western perspective, the types of people that Beijing attracts tend to be much more interesting characters. Beijing can be so harsh, that after many years of living here the people you see and recognize that have stayed in my experience are all quite interesting people. If you love Beijing, it's certainly not because it provides an easy or comfortable lifestyle. You are here for other reasons. For us, we chose Beijing because it is the cultural capital, it is the political capital, it is the art capital, and these are the things that are important to BAM.

What does BAM stand for? Does the name arise from your initially explosive and geometric Jacks-like installation designs? What does it say about your overall mission and work in the field of landscape, architecture, urbanism, and art?

Ballistic: The term ballistic refers to our explosive and energetic exploration of a variety of design and art fields without regard to traditional disciplinary silos of practice. When BAM discovers a new and interesting mode of working, style, or field, that new realm is typically not explored lightly or dabbled in but is pursued at full charge.

Architecture: Architecture refers to an architectural methodology or process by which the work is created – utilizing or contrasting with the tools, processes, and language of architecture in order to create our work. Design, unlike the arts, is defined by constraints, the questions of how one can come as close as possible to an inherently unachievable ideal is the central mantra for all design. An architectural method provides a rigor through which BAM is able to explore our schizophrenic interests.

Machine: Machine quite simply refers the intensity and unwavering drive to work and create.

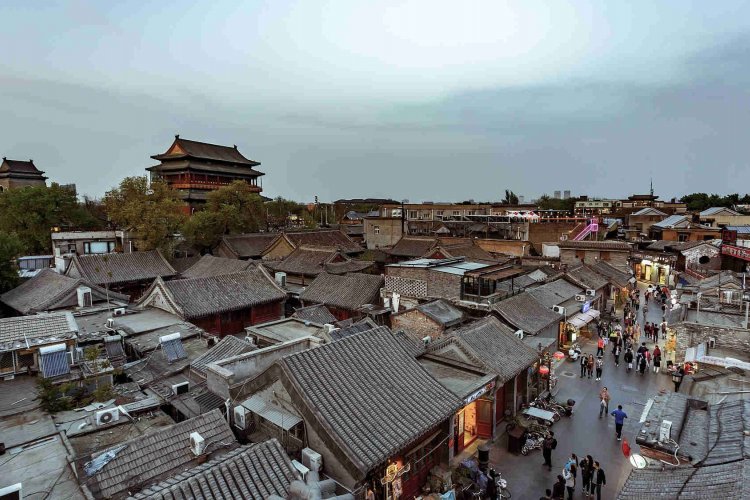

BAM is about evolution. BAM started as a group of like-minded individuals in architecture school interested in installation art and publication as a means to create and activate community. This in part was a rejection of traditional methods by which architecture is taught, which imply that architecture is the center of the world and the highest of art forms. Our initial interest in installation work leads us to gravitate away from the traditional architecture and toward the field of landscape, which inherently deals with a more social agenda and less controllable conditions. However, BAM’s evolution toward landscape was not a straight line. In our initial years starting out in our hutong in Beijing near Gulou, we had no clients and no money. At this time we did many small interventions, funded and installed by ourselves. Eventually, these interventions allowed us to land more significant art installation commissions. These installations were always associated with some kind of indoor or outdoor public or semi-public retail space commissioned by developers.

While always aiming to work on a large scale in the public realm, our exposure to retail environments and clients guided BAM's evolution toward the more ephemeral and fast-paced world of seasonal installations. The world of seasonal installation exposed BAM to a side of the Chinese culture which cannot be gained when viewing through the lens of design or art. The designing environments and objects which were meant to conjure associations with festivals such as Mid-Autumn Festival, Spring Festival, Christmas, and the like allowed us to tap into the story-telling aspects of Chinese culture. The continued exposure to the world of retail allowed BAM access to more development clients. With the completion of BAM’s first landscape project, a collaboration for a small garden as part of the Beijing garden expo, BAM was able to push more deeply into the realm of the public landscape. This, combined with our learned knowledge of retail, provided us the opportunity to capture retail landscape projects. These then snowballed into landscape projects of all kinds – hotels, resorts, malls, and eventually larger scale works such as parks.

Unsatisfied with the cookie-cutter-based methods which developers employ to create retail environments, BAM has started to push into even larger scale works pushing our agenda into urban design scales. Yet, as BAM is poised to evolve into one of China’s leading landscape and public-oriented design firms, the field which we find ourselves in is beginning to reveal its boundaries and constraints. Boundaries are not something which BAM is comfortable with, and by virtue of this, BAM is also not comfortable being defined by any given field of art or design.

Describe some of the logistical and cultural differences between doing what you do in the States and China. What are some of the benefits of working in Beijing?

We believe that in China, the landscape is actually a better field than in the United States, because the Chinese culture is developed from a garden culture. Garden culture is where people would make paintings, write poems, it’s where governors would govern. The garden is intertwined and linked to political and cultural expression. By extension, the landscape is understood as a place that should be designed, a cultural medium. In the United States, it’s not like that. The United States believes that the landscape is not a place for cultural expression. American culture is still a young culture and it hasn’t really blossomed to the belief that the landscape is something that represents culture. In China, that idea is ingrained in what we do, people see the landscape as critical to culture.

Furthermore, we feel landscape is the most important field of design in China because China already has great architects. Yet when observing the city, it is clear that architecture isn’t really helping. Thus, landscape architects are much more important, because they deal with everything outside of the buildings. The landscape is essential for the Chinese cities to really start working well. There must be a lot more investment in landscape design and innovative thinking in landscapes. Landscape architecture in China is the most critical design field right now. If we were practicing in America, we would most likely be designing buildings, but in China, it must be landscapes.

You specialize in landscape architecture and design. Can you give a few instances of what you would consider Beijing’s best examples in this field?

Beijing has some beautiful tree-lined streets. Many of these tend to be within the Second Ring Road, around the older embassy areas, as well as a few other places in the city, but these types of landscapes can be quite majestic when they are not packed with traffic.

Beijing also has beautiful parks. Ritan, Tiantan, Jingshan, and the Summer Palace are among our favorites. It is important to note that any park is essentially a good park, and Beijing could definitely use smaller-scale pocket parks, but the contemporary parks of the city such as Chaoyang Park, while a necessity, have much to be improved. A park should be a connective element in a city, Chaoyang Park often acts more as a barrier. A limited number of gates, south, west, and north, prohibit users from traversing diagonally, ticketing booths keep out anyone who isn’t planning to go for a significant amount of time, pets are not allowed, bikes are not allowed, this excludes huge numbers of people. Not only this, but the insensitivity of development within and around the park deteriorate its potential for being a respite from the intense urban condition of the city.

The Solana Mall is very intrusive into the park's space, yet is not able to capitalize on that intrusion; it is not possible to walk from the park to Solana directly, nor are cafés or restaurants able to take advantage of being park-side. An entirely needless amusement park occupies a very central part of the park and seems to sprawl endlessly. We are not against the programs of amusement, and having an amusement park could be fine but it doesn’t have to so invasively occupy seemingly every part of the southern part of the park. Beijing has great historic examples of landscapes, but the contemporary ones are seriously lacking. One of the worst landscapes in Beijing is the Guomao intersection and that is why BAM has taken it on as a theoretical project to reimagine the intersection as a park, while still maintaining all of its current functionality with regard to auto, pedestrian, and metro traffic.

From an architectural or design perspective, what do you think of the government’s unabashed approach towards remodeling and repurposing Beijing’s hutongs? If you took the reins, what would you perhaps do differently, or the same?

Urban renewal has happened countless times inside of the city’s Second Ring. Whatever changes are taking place there now have only a minor impact compared to the wholesale removal of the original city wall in the 1970s. The city is in a way like how the Chinese understand nature – undergoing a constant process of change and renewal. While we, of course, bemoan seeing aspects of the Beijing we first met in 2005 disappear, we don’t think anything can truly hamper the spirit of the city. Attempting to freeze the hutongs in time is also not desirable and unrealistic when owners have seen their property values skyrocket in the last decades.

All that being said, we do have big problems with gentrification and privatization of public spaces. As we are advocates for the landscape, we are also advocates for those who have less. A building is for the people who can afford it, a park should be for everyone. A residential compound is only for a few, but a street is used by all. If you work in the landscape, these are inherently your concerns. I think we would prefer not to see those with less being uprooted and further diminishing what little they have. By extension, landscapes like the Guomao intersection or Chaoyang Park should really be the focus when considering how to clean up the city. Washington DC is a horrendously sterile city, it would be quite unfortunate if Beijing was looking to that as an example of what a capital should look like.

And finally, what are you currently working on? Where can we see your designs in Beijing now or in the future?

BAM’s built Beijing projects are: Beijing Garden Expo in Fengtai District, a linear park of the Yihezhuang stop in Daxing District, and the playgrounds behind the Indigo Mall in Jiuxianqiao.

Catch dART's and BAM's collective 10 Years of Dumb at Migas on September 15. Tickets are RMB 70 at the door, RMB 50 in advance. See more of BAM's work on their official website.

Images: dART, BAM