Talking Tech: Bridging the Generational Tech Divide and a Foreigner's Daxing Rant

What's the latest in clean breathing innovation? Who is using your data? When will the drones deliver your mail? Keep up with the latest circuitry in our column, Talking Tech.

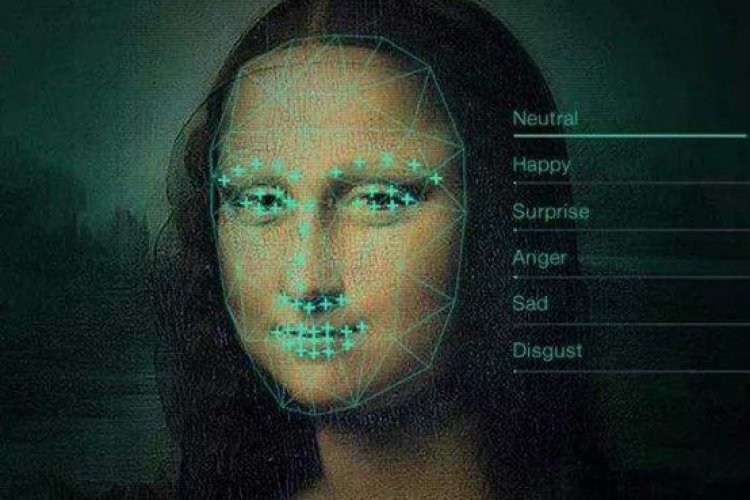

China addresses its digital refugees

Anyone who once held a Nokia phone knows just how quickly technology has progressed over the past couple of decades, and Western cultural critics have been quick to debate the implications for the generations that have grown up in this world of screens, feeds, and streams – the so-called digital natives. But in China, where youth-centric thinking is far less prevalent, there is more room for discussion in the public sphere about what American scholar Wesley Frye has called digital refugees, or those that technology has left behind.

Fryer's work may have received limited attention in his own country, but China is certainly paying mind. More than a difference in cultural mindset, however, the fact is that China has to act in favor of digital refugees due to how rapidly the country's digitalization of services is progressing, resulting in no shortage of headaches for elder Chinese as everything from purchasing tickets online, verifying their identity at the bank, or even making a simple purchase at the supermarket goes digital. Add on the ubiquitous health-code of the pandemic era, and you've got yourself a recipe for extra-thick frustration.

In response, the government has stepped in with several new policies and regulations in the hope of bridging the gap between the elderly and the new technological environment they find themselves in.

As a matter of priority, health code reform has come first in order to prevent the code from becoming an insurmountable obstacle to travel for elders who do not use smartphones. The solution is to integrate the health code with the metro card, ID card, and other such documents.

As for local transport, taxi companies will be required to maintain taxis that stop for street-side wavers and telephone reservations, thus preventing a full DiDi-ification of the industry. Hospitals too must keep manual service windows open and will have to allow elders’ relatives, friends, or private doctors to register them. And finally, the government has reiterated that no vendor is allowed to refuse to accept cash, especially the ones that provide public services.

Moreover, programs will be launched to educate elders about cashless payments, as well as to warn them of modern fraud schemes that abuse such technology. Private apps and websites are also being asked to join the effort. About 100 websites and apps have received requests from the government to revise their interface designs to be more elder-friendly.

Foreign wanghong rants about digital divides in Daxing Airport

Recently trending on Weibo and Bilibili, a German KOL called Leo released a video addressing a different type of digital divide. In a five minute rant on his experiences at Beijing's Daxing International Airport, which he claims has embraced technology for technology's sake, without considering the implications of removing the human factor from the airport's service.

"Everyone would have to go to the machine," he says describing the efforts to obtain his boarding pass. But he couldn't get the machine to accept his passport. "And I don't think it's because I'm too stupid," he says, adding, "even though I wouldn't rule that possibility out."

But the problem wasn't just that the machines are faulty. It's that the airport is over-relying on these machines, having apparently done away with service counters altogether. That sentiment was confirmed when he finally found a live human service worker – who was completely overwhelmed with requests for help.

The video has been viewed more than 150 thousand times within four days on Weibo and got more than 700 comments at Bilibili. Most netizens who commented felt that they could relate to Leo's plight. According to commenters, customer service hotlines are among the greatest offenders, forcing customers to talk to a robot who is hardly of any help for 20 minutes before it finally transfers you to a customer service agent.

Read: You May Pay More (or Less) For Your Next Train to Shanghai

Imges: Hubei Daily, Aginginplace, Bilibili