Postcards From Dashilan: Retracing the Development of Beijing’s Former Commercial Hub

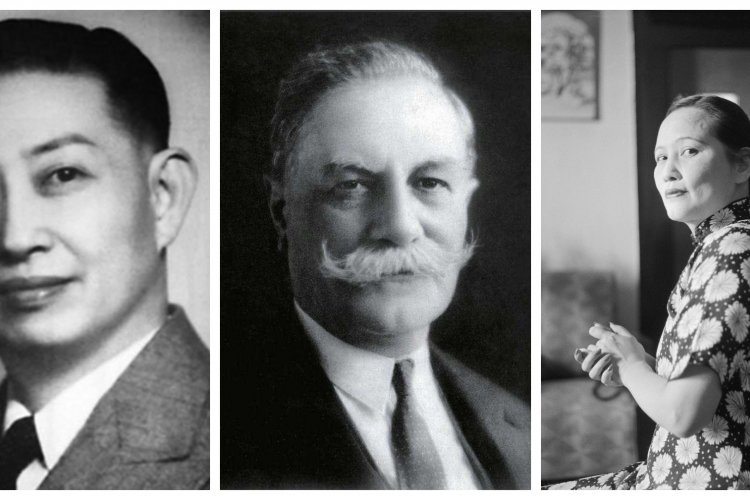

Beijing has seen a lot of changes this year, but is this something new? Beijing has always been in a state of flux. Sometimes the busiest areas in one era give way to quiet lanes in another. Danish historian Lars Thom of Beijing Postcards has spent over a decade researching the evolution of the capital, tracking the rise and fall of the city’s residential and commercial centers from century to century.

Thom’s research has recently focused on Dashilan, where Beijing Postcards has its new public history space. The neighborhood is a warren of hutongs and lanes located just to the southwest of Qianmen Gate and today’s Tiananmen Square. The area was once one of Beijing’s most vibrant commercial neighborhoods, along with Wangfujing and Xidan.

According to Thom, “Items such as leather, shoes, watches, and bicycles could be found in the neighborhood stores and shops. And the lanes have been a destination for those seeking specialized commodities since the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).”

On a recent research trip to Japan, Thom found a book of Beijing souvenir maps published in 1982, a time when Beijing was just emerging from the Mao era. On the map, shops are represented by icons, watches for sellers of timepieces, bicycles for those selling pedal-powered transportation and … well, you get the idea.

“It’s not that old, but this book of maps is a fascinating historical document,” says Thom. “It triggers so many memories. You show it to people in the neighborhood and they immediately can recall such-and-such a shop, long since gone, but alive in the collective memory of the local residents.”

According to Mr. Liu, who Thom interviewed for his new research project on the commercial community in Dashilan, the main shopping drag would be an endless stream of consumers. Shoppers would get caught up in the flow of humanity which descended on Dashilan on a daily basis, one stream of pedestrians flowing west, another rolling east, each on their own side of the streets, so thick were the crowds.

And yet today, areas such as Wangfujing and Dashilan are tourist attractions or afterthoughts to the current generation of Beijing uber-consumers.

The beginning of the end, according to Thom, was the opening of the new Beijing Railway Station in 1959. The old train station, built in 1901, was located just outside the Zhengyangmen Gate, close to the Dashilan Neighborhood. The area was the often the first point of arrival for visitors to Beijing and the neighborhood thrived with not only shops, but also guesthouses, taverns, restaurants, temples, theaters, and a lively red light district.

The construction of the new railway station, 2.5 kilometers to the west, shifted the commercial center of gravity in the direction of nearby Wangfujing. But even up until the end of the last century, Dashilan remained an important and bustling space for trade, even as the construction of gleaming new malls and shopping plazas in Chaoyang and beyond signaled a new era of consumer culture.

It can be hard running a hutong business in 2017, but in the days of Old Peking it wasn’t any easier opening a shop in your local hutong – in fact, it was in many ways much more difficult.

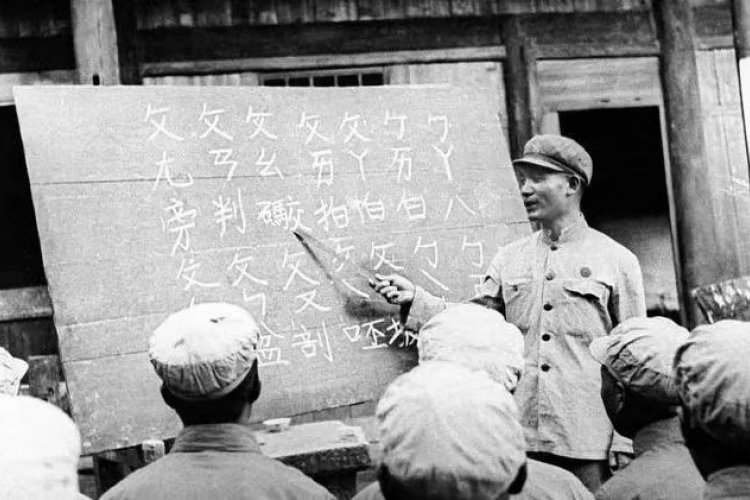

Thom is researching how commercial guilds controlled the trade in different products and services and regulated the opening of shops and businesses in Beijing. “You had to be approved by the guild to learn a trade. There was a strict hierarchy. You started as an apprentice and even that wasn’t easy.

You needed to not only find someone to hire you but to also stand as your guarantor. There were quotas and licenses. Just opening your own shop without going through the guild system just didn’t happen.”

Renegade shop owners – or bespoke cocktail makers – who tried to buck the system could find themselves in deep trouble with both the city authorities as well as with the guild bosses the authorities relied on to keep economic order.

This system persisted throughout the first half of the 20th century, ending in 1949 with the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

Thom takes a long view when looking at the changes in the city this year.

“Going back to the 1950s and 1960s, a lot of the development was haphazard and chaotic. Cleaning up the city makes a certain amount of sense; you can’t develop until you do. But the way it has been handled hasn’t always been carried out humanely.”

Currently, Thom is working on developing a walk based on his most recent find, combining interviews with local residents and archival research based on the establishments listed on the 1982 Dashilan map.

“One place you can find a lot of stuff is Taobao,” Thom says as he holds up documents and artifacts from a long-since defunct local factory. He found the documents by doing a search for the factory name on the popular e-commerce platform and was amazed at what was available.

Currently, Thom is displaying some of these artifacts at the Beijing Postcards Public History Space located at 97 Yangmeizhu Street, Dashilan as part of their Beijing Arrivals exhibit. Discover more at Beijing Postcards' official website.

This article first appeared in the Nov/Dec 2017 issue of the Beijinger.

Read the issue via Issuu online here, or access it as a PDF here.

Photos: Jens Schott Knudsen/Beijing Postcards