Film Lovers, Attention: Chinatown Cha-Cha Is Screening in Beijing!

Winter’s coming, dear reader, and like American author Ottessa Moshfegh, I harbored hopes of rest and relaxation. Surely my socials were bound to subside now that we’re about to freeze our buns, right? Wrong. Hutong rooftops may indeed sleep until next year, but then there’s the wild indoors, and it seems like I’ll be forced to fish my thermals and venture back into the streets of Beijing, for this dang city truly never stops serving me fun.

Case in point: next week I am going to the movies. The feature-length documentary Chinatown Cha-Cha, by Chinese director Luka Yuanyuan Yang (杨圆圆), is about to be released in China, and on Tuesday, Nov 5 at 8pm, Capital Cinema (Xidan branch) is hosting a screening after the premiere. Watch out, because there’s a bonus: the producer and protagonists will be present for a Q+A session, too! Chinatown Cha-Cha is a really special film exploring themes of familial memories, Chinese diaspora and the emotive journey back to one’s roots. It has been nominated for two Best Film awards and the Youth Jury Award at the Pingyao Film Festival 2024, and it was part of the Official selection at the Hawaii International Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Kau Ka Hōkū (Shooting Star) Award to international emerging filmmakers.

Tickets for the Chinatown Cha-Cha screening on Tuesday will be a mere RMB 45, so there really is no excuse. Until then, we got to interview Yang herself. Go get your popcorn and bevy of choice ready, and plop on your seat for this insightful conversation on filmmaking, personal stories and creation.

Hello, Luka. I am so looking forward to your screening. Chinatown Cha-Cha starts with former nightclub dancer Coby Yee and her decision to get back on stage once again after joining the senior dance troupe Grant Avenue Follies, once part of the golden age of San Francisco Chinatown. These seasoned interpreters band together for one last tour, bringing together a cultural renaissance of sorts for otherwise dwindling Chinese communities in the US, Cuba and China. This was Ms Yee’s final journey before her passing at 93 years old, and it is particularly emotive when we see her return to China, her father's homeland, which represents a chance for her to reflect on her family’s memories and contemplate the startling transformation of urban landscapes. How does it feel to see Coby Yee in motion on the screen now that she’s gone? She was a trailblazer and an indomitable spirit. What do you think is her legacy?

Documentaries, to me, are time capsules of sorts. They can preserve lives, memories and personal histories. In Chinatown Cha-Cha, Stephen King, one of the members of the cast, addresses this in a beautiful scene where he contemplates the unpredictability of life. Ultimately, though, he concludes that life can be preserved in films.

In the premiere at the Hawai’i International Film Festival, Stephen, Shari (Coby’s daughter) and Coby’s niece got to watch the documentary for the first time. I got really emotional when Coby’s niece brought up her favorite part in the film. She said that we had managed to capture Coby just as she was in real life, for instance, her signature gesture when eating noodles—she would point her little finger. Her breathing, too; the way an elderly person breathes. This really impressed me, because it’s important and so meaningful; only a relative would be able to notice the way their loved one breathes. It’s so touching that Coby’s niece noticed it. Coby’s breathing is a sign of life, and her relatives were there, paying attention to these details.

As for myself, I feel such overwhelming gratitude that we got to spend time with her in the final years of her life. She was larger than life, and her personality permeates the whole film. We had lots of fun during the tour, and we really feel fortunate to have been there with her.

That’s really meaningful. Your work typically deals with an interest in the Chinese diaspora, stemming from your own observations on what is often the “cultural limbo” of these immigrants both in their motherland and in their countries of destination. Within this scope, Chinese women occupy a prominent space in your films. How do you think the complexities of the Chinese diaspora converge on its female representatives? What are the peculiarities of their experiences? And how do your visual language and documentarian approach address these themes?

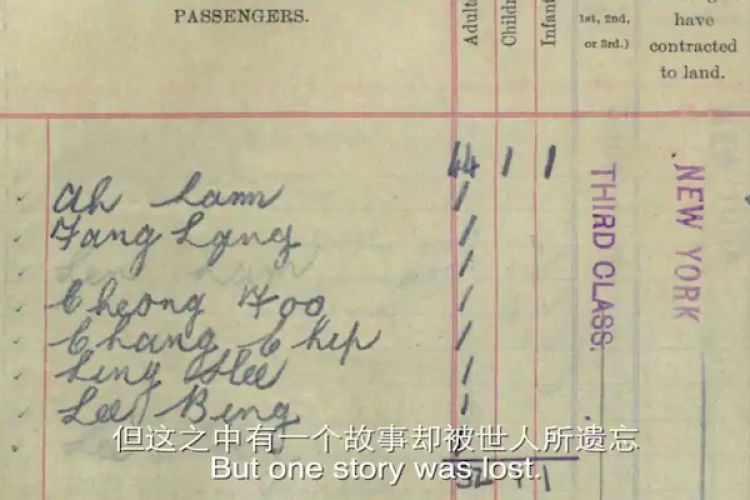

So there’s a historical context to this. In the United States, a Chinese Exclusion Act was signed in 1882 which prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers for a decade. It was, in fact, the first significant law restricting immigration into the United States, and it was renewed and strengthened in 1892 with the Geary Act and made permanent in 1902. It remained in force until the passage of the Magnuson Act in 1943. So, during this time, Chinese migrants in the US really didn’t have many job opportunities out of a few restricted spaces. They would be allowed to help build the railroads, and then they could open restaurants and laundromats, but not much more.

Coby Yee herself was born in Ohio, Columbus, to a Chinese family, and her parents were first generation laundromat owners. Coby wanted nothing of the family’s business. Instead, she loved music and dancing and longed to become a tap dancer. This was simply out of reach for her as a child of Chinese migrants, though. But an opportunity came through when she was introduced to the burlesque dance scene in San Francisco’s Chinatown. She was told she did stand a chance, if only she’d be willing to bare her legs and shoulders in her performances. This wouldn’t have been Coby’s first choice, but she eventually decided to embrace it all as a fashion show. She would display her creativity in her performances, and eventually, she found a way to negotiate her own boundaries. At a time when feminism and multiculturalism did not exist, but rather it was the West versus the East, she was ahead of her times, very avant-garde. Her fashion was a melting pot of influences and styles.

Now, don’t get me wrong, the early 20th century was a time fraught with hardness and discrimination. But we should concede equal attention to the great resilience and creativity that so many ordinary people displayed in such times. It was a moment in history where many layers converged.

If I recall correctly, Chinatown Cha-Cha is actually the main trunk of your multifaceted research-based project Dance in Herland, which is made up of five short films, photographic documentation and archives and a publication along with the documentary. This must have felt like a very rewarding yet all-encompassing feat. When did the project start? What were your main challenges? And did you have any unexpected anecdotes along the way?

The project started in 2018 and was an unexpected turn to my background in visual art. I’d always worked in museums and galleries, and then in 2017 I was awarded a fellowship by the Asian Cultural Council (ACC) to pursue an art residency in the US. Initially, I was to research Chinese female figures in the sound and visual culture of the 20th century. Think Anna May Wong, except I figured there had to be more.

Eventually, my interest in history led me to Coby Yee and the Grant Avenue Follies. Talk about love at first sight! I realized that nothing but a documentary would honor their story. It’s not like this was easy for me to tackle. No experience, no budget, no team. But I did have my studies in photography and a great deal of enthusiasm. And when I met my co-cinematographer, Carlo Nasisse, we were finally set.

This documentary is a labor of love by a small team whose members fluctuated depending on the location. We had a reduced group of people helping out in Cuba and China, and even during production, our largest team was just four people. But I was mostly by myself or with Carlo. As you may imagine, it wasn’t easy, but it also made for a fairly intimate relationship with the documentary’s protagonist. That wouldn’t have been possible with a larger theme.

Another remarkable challenge was funding. Making a feature film in China isn’t easy, and at some point, I realized I needed more money to finish Chinatown Cha-Cha. So after a few failed attempts to raise funds, I started a Kickstarter campaign that went viral in China, with 500,000 views in one week. Help poured in, more professionals and producers joined the team and now, after three years, we finally get to watch Chinatown Cha-Cha on the big screen here in China.

Excellent, what an accomplishment. It only makes sense that Chinatown Cha-Cha will be especially poignant to diasporic Chinese and adjacent communities. Many of us are now actually migrants in a foreign country ourselves, and yet I am acutely aware of the distance that mediates between our experiences in terms of a moment and place in history, privilege and socioeconomic discourse. With that respectful disclaimer in mind, though, I think the general audience can still really relate to some of the themes explored in this documentary. The passing of time, the unrelenting transformation of the spaces where we were once rooted, unsuspecting of the forces at play… What is the one message, if any, that you hope anyone will walk away with after watching Chinatown Cha-Cha?

You know, when I reflected on the audience’s reaction to the film, both in the US and here in China so far, it was one that spoke of a universal feeling of warmth. Coby and the Follies’ energy was inspiring to the public, which was quite heartwarming. These senior ladies had a message—life isn’t over when you turn 60, or when you go through whatever failure. No curveball can bring you down permanently. You can always start again, stand up and dance. I think that was really inspiring.

Though, I will also say that the message depends on the watcher. Everyone can take whatever matters most to them out of this documentary. Some are very into the history side of it, while others will resonate more with the theme of identity. Untold stories will come first to some, while others may catch on the long-lasting friendship between these women.

Beautiful. The documentary genre is one that involves a very specific brand of storytelling. It requires filmmakers to spin or collect stories out of specific, tangible realities, often with an intense thought process behind them. Do you think this bears particular relevance in our current times? And is there any documentary method that we can carry into our own personal lives and reflections on the self, as well as on our interactions with the world around us?

So we’re living in a time where we are constantly bombarded with images and we get to interact with them in ways that would have been unthinkable in the past. Take my own case; I had no background in cinema, but all I needed to start out was a set of gear that was professional but not crazy expensive. Even a party of two like my tiny team could handle them. The important thing here is that I wanted to share a story, and being passionate about this helped me overcome all difficulties.

In a way, I actually took a page from Coby’s book in that sense. Her story and spirit greatly inspire me. They remind me that we should not allow the past or whatever uncertainty to hinder our future. We should aim at doing whatever we aspire to accomplish. So, if you also feel an urge to shoot a documentary, go at it with whatever resources you may have, even if that’s just your phone. Your platform can simply be your social media account. Everything feels possible right now in that way.

At the end of the day, it’s really important that we leave a trace of our lives, a legacy. With so many methods and ways to go about preserving each individual’s memories, we should really take it upon ourselves to rescue all this precious material from oblivion.

The screening of Chinatown Cha-Cha will be taking place on Tuesday, Nov 5 at 8pm at Capital Cinema (Xidan). Tickets are RMB 45 and you can register by contacting Laura Amaranta on WeChat (ID: LauraAmaranta).

Capital Cinema (Xidan) 首都电影院(西单店)

10F, Xidan Joy City, Xidan Bei Jie, Xicheng District

西城区西单北大街西单大悦城10层

Images courtesy of Luka Yuanyuan Yang