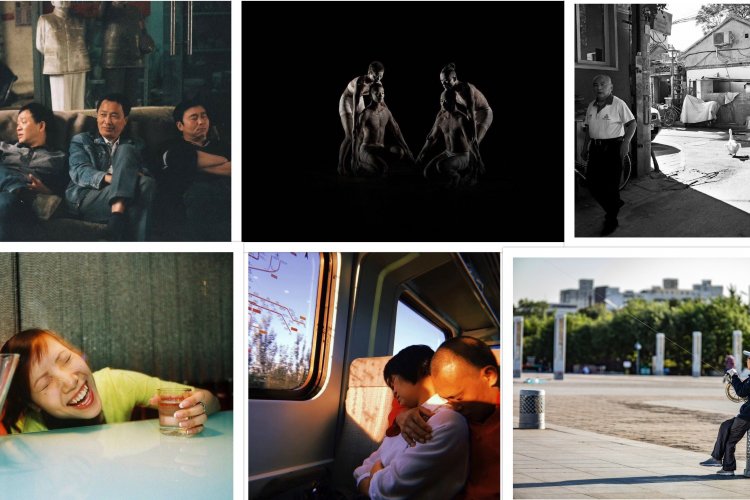

Beijing Lights: I Gave My Youth To This City

This post is part of an ongoing series by the Spittoon Collective that aims to share some of the voices that make up Beijing’s 21.7 million humans. They ask: Who are these people we pass in the street every day? Who lives behind those endless walls of apartment windows? These interviews take a small, but meaningful look.

Note from the editor: Wang Haijia is a delivery worker. He is of medium height, with slightly high cheekbones. His face is reddish from exposure to the weather, which makes him look older than his age.

Wang Haijia, male, 42 years old, from Hebei, delivery worker

I was delivering food on a rainy day. I was in such a rush that I rode through several red lights to make it on time. After the job, the app notified me I was tipped 15 kuai. On my way back, I felt warm despite the rain.

I’ve been working in delivery for a long time, getting tipped is not something that happens very often. Sometimes when I’m late, I might get scolded by the customer. But most of the time, people treat me nice. Some customers even message saying not to rush and to put safety first.

Before working as a delivery man, I did many different jobs. I dropped out of school to work at construction sites before I finished junior high. I was carrying bricks in the beginning, and worked as a bricklayer sometime later. It took me a few years to do more skilled work like installing supports for buildings.

Dangers await everywhere in this kind of job. I was removing supports when one of them suddenly fell off on my head. I was out cold. Hospitalized for over two months. The accident haunted me. I refused to work on construction sites ever again. My life outweighs the money I’d make.

I came to Beijing, first waiting tables. Then I worked as a safety guard. It was a boring job. I was standing for over ten hours a day. Next was a Japanese noodle restaurant for a few years...I kept switching among different jobs until I returned home to get married years later.

After my son was born, I stayed home to be around my wife and kid. Back home, there’s little work outside the steel factory. And it’s hard work. I was on regular night shifts in a horrible work environment. The pay wasn’t even good.

I worked there for two years. Meanwhile, my brother-in-law was a delivery worker in Beijing. He suggested I join him. He said we can have flexible working hours and get paid better than the factory. That’s when I started my current job.

I leave my place around 8 or 9am every day, working until 10pm. I usually grab some quick food like jianbing from street vendors or eat at those food stands for take-out only. They usually give us a few RMB discount. I spend at least 30 to 40 kuai on food every day.

Our pay for each delivery depends on the distance. From what the customer and the restaurant pay for delivery, the platform takes a big cut. We might only get 5 kuai out of a 15 kuai job.

We also need to worry about fines. Arriving late is one of the most common fines. Sometimes we’re only a few hundred meters away from our destination, but it’s already the designated arrival time. If we confirm our arrival early out of desperation, the system’s GPS will know and trigger the fine. But if we don’t confirm, then we’re counted as being late, and we get fined anyway.

All sorts of things can deter us from completing a job on time. Sometimes the customer has given a wrong address or phone number, or the restaurant has relocated but the GPS navigated us to the old address. But no “excuse” is allowed, if we’re late, we get fined, even if we’re not to blame.

Also, when customers file a complaint against us via the platform, we get fines too. We could get fined 50 kuai for a serious complaint. A bad review on the platform costs us 3 kuai, but if we get a five-star review, we get nothing as a reward. It’s cruel and unreasonable.

We’re sandwiched in the middle. The platform can take money from us and can fine us; the customers can be demanding and can file complaints against us; the restaurant can refuse an order and can be slow to provide food. We’re the ones with the least voice and the most restrictions.

Things were easier even just two years ago. There were more delivery service platforms. But now the industry is dominated by two major platforms that hold all the resources. No competition guarantees they can keep decreasing pay while shortening the time limits.

When things are good, I can get 40 or 50 jobs per day. But many days, I’m only able to get 20 or 30, which is less than 200 kuai for a day’s work.

When having a bad day, like when I get complaints from the customer, I feel so vexed and frustrated. I’ll ask myself why I’m still here doing this job. I’ll consider going back home.

But then a second thought would immediately wake me up: What could I do if I went back?

For people like me, our common dilemma is that where we call home, there are no jobs; but where there are jobs, it can never be home for us.

If we could choose, who would want to be far from family? It’s just we can find no way to earn a living back home.

My son is 7 years old. He is about to attend primary school. I try to provide for him as best I can. I count every penny I spend here and only rent a place that costs me 500 kuai per month. That’s probably the cheapest place one can find in Beijing nowadays. There’s nothing but a bed in the room. I can only lie down when I walk in. I don’t have any luggage but several clothes that I keep in a bag and put under the bed. I take my bath at a nearby public bathhouse which costs me 20 kuai each time and use the landlord’s hand-washing sink to brush my teeth every morning.

During the daytime, I’m too busy to think that much. But before going to sleep at night, all my life problems bubble up, unsettling my mind. I think about how I have parents to support and a son to raise. The family responsibilities on my shoulder are only getting heavier. I’m over 40 years old, but still good for nothing.

I came to Beijing in my early 20s. I devoted all my youth to this city. After so many years, the city has paid me next to nothing in return. There is nothing to my name. Except for the bed that I pay 500 kuai per month to secure, my hands are empty.

READ: Beijing Lights: Nobody Is Born to Be a Thief

Image: Spittoon Collective