Mandarin Monday: Capitalized Chinese Characters? What the Hell are Those?

Mandarin Monday is a weekly column where we help you improve your Chinese by detailing learning tips, fun and practical phrases, and trends.

Capitalized Chinese? How does that work?

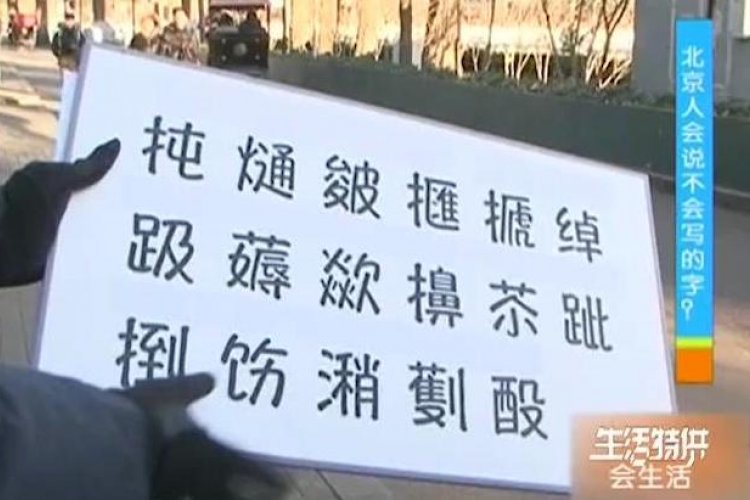

Alright, so we're not talking about literal capitalization. This has nothing to do with beginning a sentence or proper nouns. Neither, however, are these special characters some Gen Z internet slang. In fact, you may already be familiar with them, assuming that this cashless society hasn't cut you off from banknotes entirely. We're talking about the numeric characters written by bankers of old in order to minimize forgeries. Altogether, these characters cover the numerals from one to ten, with a couple of extra units in the mix, specifically 100 and 1,000.

Before we dig deeper into the history though, let’s take a look at these so-called capitalized characters and see what they originally meant outside of this numerical system.

壹 One; The character originally meant single-minded

贰 Two; The character originally meant treachery

叁 Three; The character was originally an alternative way to write 参 cān, which means join in or grant an interview to someone

肆 Four; The character originally meant to act willfully and wantonly

伍 Five; The character originally meant a squad consisting of five people

陆 Six; The character originally referred to a flat land above water

柒 Seven; The character originally meant varnish or lacquer tree

捌 Eight; The character originally meant a farm tool similar to a rake

玖 Night; The character originally meant beautiful black jade

拾 Ten; The character originally meant to pick up

百(佰); One Hundred; The character 佰 originally meant centurion

千(仟); One Thousand; The character originally meant chiliarchy

零: Zero; One of a kind among these numerical characters for only being endowed with such a numerical meaning around the 19th century. It originally meant to drizzle or referred to a minor part of something.

To understand the reason behind these capitalized characters in accounting and other documents that involve heavy use of numbers, we need to turn our clocks back a few centuries.

Most of these characters took on their numerical forms during the reign of the only female emperor in Chinese history, Wu Zetian, who allegedly claimed to have coined the character 曌 zhào (which refers to the time when both the sun and the moon cast their light). This habit was passed on to the Song Dynasty, wherein most governmental documents adopted this numerical system to prevent people from falsifying records since compared to 一, 二, 三 (1, 2, 3) they are far too complicated to be rewritten as another character by adding a few strokes.

However, this system was not mandatory for quite a long time, and to improve clerical efficiency people would use simplified words or signs in their accounting books. That is until a horrendous tale of corruption that involved thousands of government workers and unimaginable wealth startled Zhu Yuanzhang, the first emperor of the Ming Dynasty.

Before he sat on the throne, Zhu was the orphan of a tenant farmer and he had worked as a jack of all trades, even serving as a monk and a beggar. This experience cultivated a deep resentment towards venal, corrupt officers and caused him to adopt extremely harsh punishments, including adorning the court with bags made from the skin of offenders.

Besides exerting the whip of crucifixion to crush the bribe-taking officials and deter ne'er-do-wells, Zhu also required that all numbers in official documents be written in stone and in the capitalized form, to prevent tampering.

Before giving these numbers a go for yourself, there are other rules you need to remember when writing in this form, especially when documenting transactions and the like in your account book. Whenever you finish the integral numbers, add the character 元 (圆) yuán to the end to divide it from the decimals, and add 分 fēn to the end of the rest of the numbers. If there are no decimals in your record then you need to put the character 整 zhěng after 元 (圆) to mark that it's the whole amount.

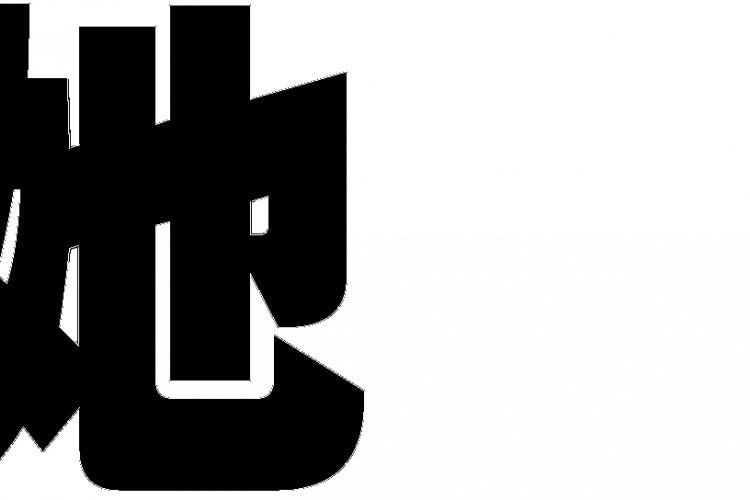

For example, on the check below, each digit is divided into its capitalized form first, then followed with the corresponding magnitude. To play around with this format for yourself, try typing some numbers on this website and see how they are transformed into the bank-appropriate capitalized form.

Do you get it? Great, now time for a pop quiz!

How would you write RMB 987654321.01 in capitalized Chinese?

READ: Solar Terms 101: Out With the Summer Bod, In With the Autumn Belly

Images: RFI, Kknews, 早游戏, Sohu