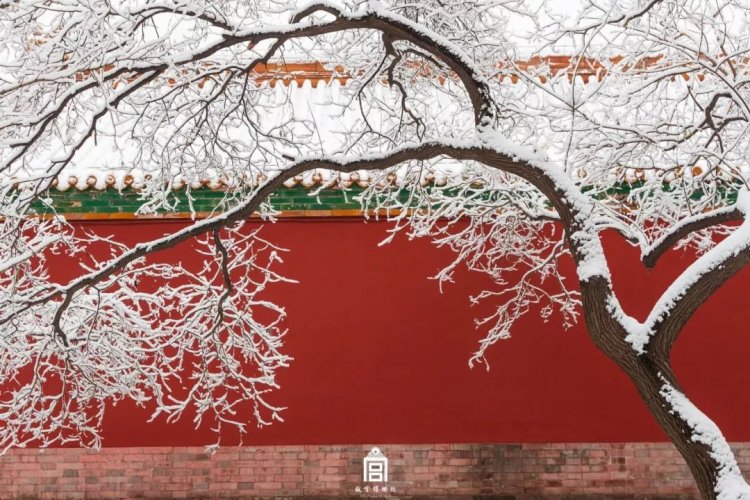

Baby It’s Cold….in Here? Understanding China’s Central Heating System Divide

As is obvious to anyone hoping to come home to a toasty room in early November, China’s heating system operates very differently from many other countries. Northern Chinese cities operate with a centrally controlled public heating system, with most cities cranking up the heat in mid-November, though the time frame can be adjusted due to an early winter or late spring, while many southern provinces are left with no heat at all. Are you curious as to how this system came to be? Let’s find out!

How did this whole heating thing get started anyway?

The centrally controlled heating policy started in the 1950s, when the government selected a line across the country, dividing China to determine which provinces would receive central heating systems and central government subsidies and which would not. Called the Qin-Huai line, the heating divide runs along the Qin Mountains and the Huai River. Premier Zhou Enlai suggested this line as the answer to China’s extreme energy shortage as the country installed central heating with help from the Soviet Union. This dividing line comes with some exceptions. For example, there is no central heating in Xinyang, Henan province, despite being bifurcated by the Huai River. Unfortunately for the chilly residents of Xinyang, about 75 percent of the population lives south of the river, so the decision was made that heating should be forgone entirely.

What is the “Qin-Huai” line? Where does it start?

The Qin-Huai line divides Henan, Jiangsu, Shaanxi, and Gansu provinces, with a portion benefitting from central heating and the rest left in the cold. All provinces south do not have central heating at all. Notably, the line divides Beijing and Shanghai, China’s main hubs. In Shanghai, temperatures dip to about 40 degrees Fahrenheit in January, while the chillier capital averages 25 degrees.

Why is this system still in place?

There is a rousing annual debate on China’s heating system, with groups advocating for and against policy changes. Despite this disagreement, three primary factors have kept the central heating divide in place. First, it’s a massive logistical challenge, as a national central heating system would be costly to build, operate, and maintain. Second, there are considerable environmental concerns over expanding China’s central heating system, as it still is largely reliant on burning coal (though natural gas and electric heating are gradually becoming viable alternatives). In addition, many southern buildings are not designed to retain heat, so will not be energy efficient. Finally, China does not have indoor temperature standards for residential buildings, meaning that there is little policy pressure to address chilly indoor environments.

I’m thinking of moving south, how do I keep warm?

Many new residential communities, especially in affluent areas like Shanghai, have installed their own heating facilities, which are then privately paid for. Some also rely on electric heat, either through multi-use air-conditioners or space heaters. The primary issue with electric heating is that its costlier than the coal alternative, meaning that China’s poorer residents may not be able to afford consistent heating.

READ: What's With All the Cabbages? Why Beijingers Stock Up on China's Hardiest Veg Before Winter

Images: Achudh Krishna (via Unsplash), Sohu