COVID-19 Lessons Learned, and Forgotten, With Poetry x Music's Anthony Tao

At its best, art expresses the inexpressible. It presents the human condition in a novel, yet uncanny way and gives voice to the myriad contradictions and truths that sit inside us. So when a pandemic sweeps across the globe, first affecting those of us in China, but quickly spreading to our friends and family back home, the need to work through a patchwork of complex emotions and anxieties becomes all the more prescient.

For poet Anthony Tao and classical guitarist Liane Halton, the duo behind Beijing-based outfit Poetry x Music, that meant putting pen to paper and fingers to fretboard, eager to make sense of an otherwise senseless situation. The result is Here to Stay, an eight-track mediation on the past, present, and future of COVID-19’s impact on humanity. We spoke with Tao about the project, and what he thinks we're likely to take away from the collective trauma of the past five months.

Please introduce yourself!

I’m Anthony Tao, 35, born in Beijing but grew up in the US. I have lived in Beijing since 2008. I’ve been writing poetry off and on since high school, and try to carve out time for it between work and other commitments.

Can you give us a little background about Poetry x Music? How did you and Liane meet, and how did that relationship blossom into this project? Had you ever done anything like this before?

Our first poetry x music performance was in June 2018 as part of Spittunes, an event created by Matthew Byrne that brings together poets and musicians. Matt was the one who had the foresight to suggest the collaboration. Liane and I realized pretty quick that our themes and processes meshed, and what was supposed to be a one-off turned into an album, The Last Tribe on Earth, which we launched at the Bookworm Literary Festival in March 2019.

Can you tell us about your and Liane’s process? Does she send you music to read over, do you send her poems to write to? Do you get in a room together with a blank slate and see what happens?

All of the above. Our first piece, “The Last Tribe on Earth,” was all Liane: she got the poem text and composed music over it and then made a video.

We try to find moments where the poem and music converge – perhaps this means she tries to catch a specific syllable in my poem with a specific note, or it means I utilize pauses to allow the music more space to express itself. Of course, there are also moments when the poetry and music diverge – we’re always playing around with dissonance and consonance.

Sometimes we’ll both start from scratch, which is how our piece “Kangding” came about.

Liane is the engine behind this project: her musicality is really special, and the way she creates new songs – the way she puts all of herself into every rendition – is inspiring.

As a follow-up to the last question, this is Poetry x Music’s second album. Did the process this time around differ from previous efforts, because of COVID-19 or otherwise?

In February, just as Beijing’s streets emptied, I felt an urgency to try to capture the surreality of what we were living through. I ended up publishing a six-part poem, “Coronavirus in China,” in the US-based literary magazine Rattle.

Shortly after, I asked if Liane wanted to compose music for it. We were both motivated to channel our observations and feelings through a creative endeavor, particularly after the virus began spreading around the world, in the US – where I grew up – and eventually in South Africa, where Liane is from.

Can you speak to the role of poetry, music, and art in times of crisis? This was obviously a cathartic exercise for you and Liane, but what do you hope your readers and listeners take from it?

It was indeed cathartic, and in that sense, this project feels quite personal. But everything we do is with an audience in mind, so we hope listeners can take some inspiration from the album, be reminded of the decency inherent in all of us, but which we must consciously foster. We also hope this gives readers and listeners a fresh take on contemporary poetry, which I believe still has the potential to move us and reveal deep truths about ourselves.

The collection opens with “In the Streets” where you write, “To survive humans, you have to give up / humanity – so says the tyrant within.” Following that, in “In the Air” you write, “We were polite / to those we did not care for.“ And yet the collection ends with “In the Heart” which begins with the incredibly pithy line, “We stopped saying hello.” When taken together, a narrative seems to emerge throughout these pieces. That is, crisis-induced unity and collectivism versus the individualism and insularity of “normal times.” Am I reading this correctly? And if so, could you speak to these themes?

Your reading is great. Here to Stay tries to capture – and creatively interpret, insofar as it can – our reality, which includes everything from individual impulses to collective actions, which of course includes organizational and institutional failings.

“In the Streets” is a critical look at the government’s decision to completely seal off Wuhan, then Hubei province. It is also a lament about how suspicion and cynicism can be sown into people’s psyches. The photographer Andrew Braun went to Wuhan after the city reopened and got all this great footage that Luke Springer ended up using to make this music video.

“In the Air” is the “love” poem in the collection – about how certain feelings make us “[forget] what we were afraid of.” It’s a very physical poem, featuring eyes and ears and bodies that we “lean toward.” Our friend Nina Dillenz made this music video.

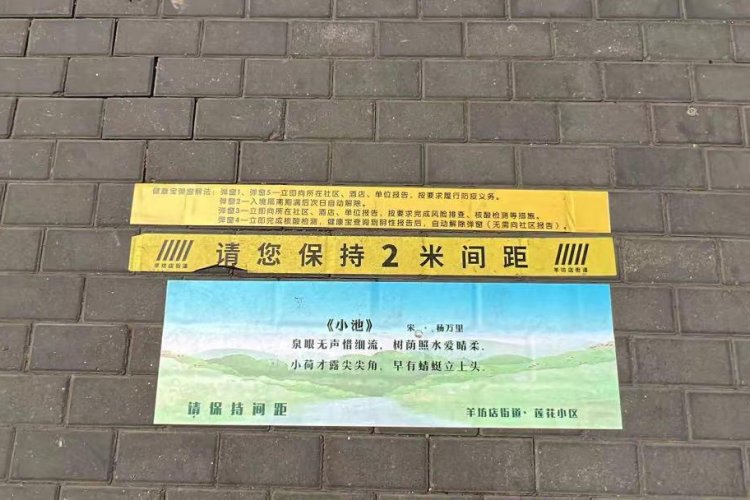

“In the Heart” is set in a near-future when the virus is “gone.” “We stopped saying hello” is a line that calls back to a previous one, from the piece “In Our Wants,” which begins, “We smiled through face masks / said hello with our brows.” The idea is that once we return to “normal” – whatever that means, or perhaps once we’ve become accustomed to our “new normal” – we are liable to default back to our old ways, which includes not noticing others, not caring about them.

I can’t help but take pity on the virus in “In the Room,” when you paint it as a “lonely / virus shivering in the cold.” It’s interesting that you make that distinction in this poem, which is obviously the most intimate of the collection. As a reader, I’m existing both wrapped in the warm embrace of the lovers and outside with the virus. In fact, much like the virus, I too feel my “nose pressed / against the window” looking in. All of which is to say, is there power and safety in love? Would you say this poem is the most personal of the collection?

I’m really glad for your interpretation. This track was inspired by a story I heard from one of my friends who became intimately acquainted with his hutong neighbors (and vice versa) during self-quarantine. I think a lot of us, during the early days of the outbreak, read a lot of news, spent a lot of time on the internet, social media, etc., and all of that can make us feel anxious, to the point that we’re no longer ourselves. With this poem, I wanted to focus on the ways we are tangible and real – to say here’s something you can touch, look at. Liane’s music is so great in this one, too – the way it moves, slithers – how energetic it is. Pay attention to her scales and the playful high note that punctuates them.

You know, when the fear was at its highest in Beijing, I read somewhere that there was a directive that advised couples to sleep in different beds at home. That’s when I suspected the response to the outbreak had gotten a little hysterical. The virus is here to stay – the album title, by the way, comes from a line in this track – and while we must all do our part to keep each other safe, we should be wary about institutions of power becoming too invasive, to the point that they’re in our bedrooms.

Here to Stay is an interesting choice for a title, and the first place my mind goes is that the lessons we learned from COVID-19, largely grounded in our shared trauma, are here to stay. Unfortunately, however, based on the analysis I put forth in the previous question, it doesn’t seem like much of anything that we learned during the crisis, i.e. shared humanity, is here to stay. At least not by the time we “stopped / holding doors.” What do you think we’ve learned from COVID-19? What about the experience and the crisis do you think is here to stay, and what do you think will fade with our memories? What have we already forgotten?

“Here to stay” has multiple meanings. I think it’s possible I’ve already given away too much with my answers above, so I’ll withhold from going too in-depth on this one, but as for what we’ve learned: I’m not sure we’ve learned anything. Or rather, what we have learned, we’ve forgotten. But that’s the human condition: We are always forgetting. History repeats itself because we can’t help but forget. We are constantly moving on from trauma, both as individuals and as a collective. Alas, that means trauma will always be with us. I’m sorry if this is a little abstract, but I do want to say that I hope this album, in ways big or minuscule, can help people remember their humanity, appreciate their creative potential and the power they have to impact others.

What does Poetry x Music have planned for the future?

We’re working on our third album, which will include a piano! David Moser, a noted Sinologist and jazz musician, will be joining us. We have some tracks already. We’re very excited about adding dimensions to this ongoing experiment we call poetry x music.

Watch this space for news about an upcoming record release show. In the meantime, check out Here to Stay on Bandcamp.

READ: Beijing Musicians Turn COVID-19 Response Up to 11

Images: Nina Dillenz