This Qing Dynasty Foodie Taught Farm-To-Table Two Centuries Before It Was Cool

Like many people, we like to read and collect cookbooks but until recently we had never used one published more than 200 years ago. That has now changed thanks to the publication of an English version of a Qing dynasty cookbook and general meditation on food and eating first published more than 225 years ago.

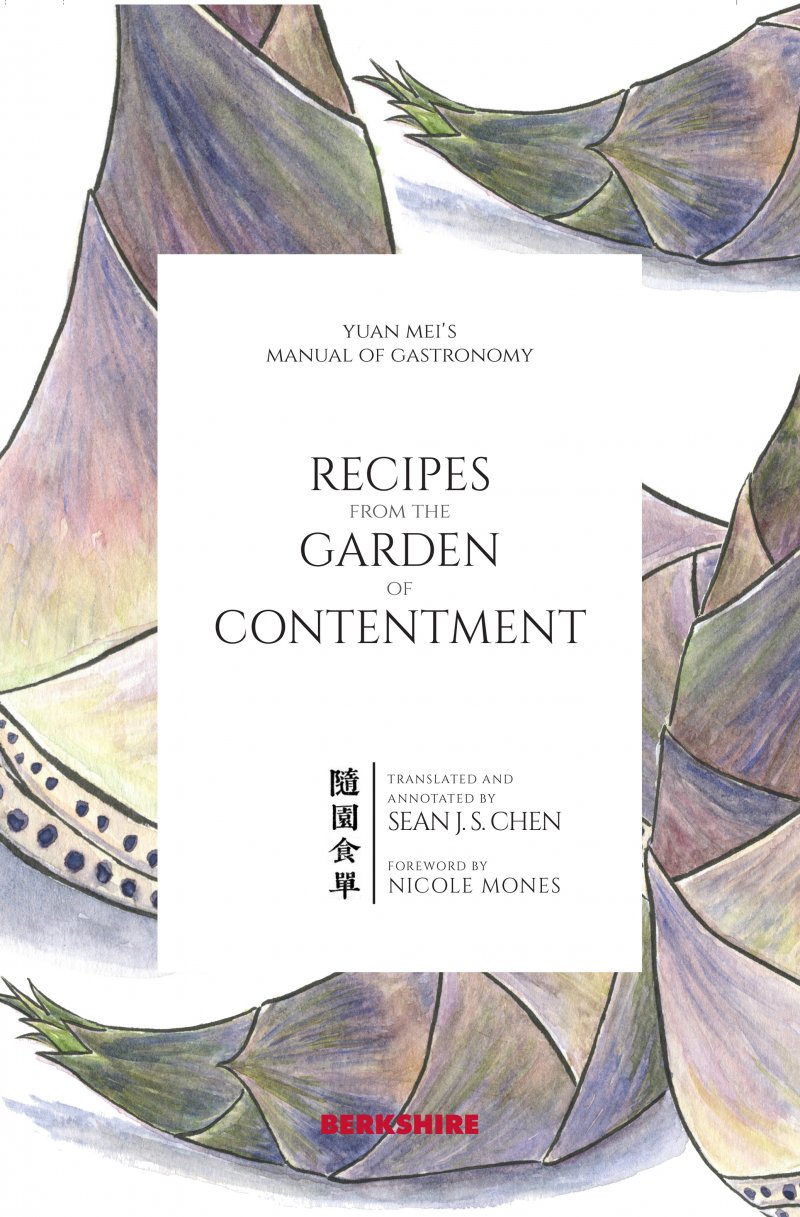

Recipes From the Garden of Contentment, known in Chinese as Suiyuan Shidan (隨園食單), is a treatise and cookbook written in the late 18th century by the Qing dynasty poet, official, and foodie Yuan Mei. An imperial bureaucrat who resigned from his post to move to Nanjing and pursue his literary and gastronomic interests, Yuan Mei has been described by Fuchsia Dunlop as "China's Brillat-Savarin." His book introduces many of the ingredients, recipes, and attitudes that are at the core of Chinese cuisine today. This English edition comes courtesy of Canadian Chinese biomedical engineer Sean J.S. Chen and a Massachusetts-based boutique publishing house Berkshire Publishing.

The book is divided into several chapters, some on general gastronomic principles and others with recipes for different categories of ingredients, along with a biography of Yuan Mei, all accompanied by beautiful illustrations.

Sadly, we haven't had the chance to cook anything from the book for ourselves, but we chatted to the translator Sean Chen about which recipes he would recommend, as well Yuan Mei's approach to food and the challenges of translating a Qing dynasty text.

TBJ: What inspired you to start translating Recipes from the Garden of Contentment? Have you always been interested in food?

Sean J.S. Chen: While working on my PhD and later working in biomedical engineering, I found myself finding respite from stress by reading about Chinese cuisines and the history of Chinese foods. One book, the Suiyuan Shidan, kept coming up time and again which pique my interest in finding it. I discovered that while there are many Chinese editions, no English translation existed. I saw this as an opportunity to improve my Chinese reading skills and learn classical Chinese and thus the project was born.

What do you think makes Recipes from the Garden of Contentment such an enduring classic?

It is a window into the past and shows us the foods eaten by people at the time, from imperial officials to commoners. However, the book is also important in that it sets out the principles of Chinese gastronomy and culinary theory in the first two chapters. In many ways, these define what makes Chinese cuisine unique, and at the same time are quite cosmopolitan and timeless. Like all great works, you can read it in different ways; a chef reading it will learn something different from a scholar.

What parallels do you see between the way Yuan Mei approached food and the way we approach food nowadays?

The way Yuan Mei approached food was surprisingly modern, for example, his emphasis on bringing out natural flavors, his emphasis on seasonality, and his conception of certain animal rights matters. One could argue that some modern Western approaches have been influenced by this earlier Eastern esthetic.

How has the book influenced modern Chinese cuisine and dining?

It is clear that what was eaten and cooked in the past is very similar to what is eaten now and that there is something of an unbroken lineage between the two. The book has also revived interest in the aesthetics of “scholar’s/literati cuisine,” where a component intellectual surprise and delight is valued beyond just the price and quantity of the ingredients.

What was the most challenging thing about the translation?

At the beginning of the project, the most difficult part was understanding the classical Chinese text and finding the right tone and methodology to translate it. However, as I became more proficient in classical Chinese, what ended up taking up most of my time was decoding the recipes and figuring out obscure terms for things such as anatomy or units of time. There was a mention of this “white tendon” that had to be cleaned from fish that took a lot of research. I also spent a lot of time figuring out the scientific names of the animals and plants referred to in the book.

Of course, tracking down two copies of the 1792 edition of the book was also a big challenge. One of them had many printing defects and damage which made a second copy essential to correct the errors. Then there was the actual process of transcribing the text in the images to computer UNICODE characters of the same form as that seen in the original text. This was more tedious than difficult, but doing it was arguably the least fun part of the project. Still, it made the book and work significantly better as a result.

Which recipes from the book have you tried and which recipes would you most recommend readers try themselves?

I have cooked several recipes including Jianshilang tofu, Chicken “congee”, fake crab, and the chicken blood. I would highly recommend the congee for its element of surprise. When you eat it, you expect plain rice congee with chicken in it but end up with a richly flavored and voluptuously textured broth. It is a rich geng disguised in plain sight as an unassuming congee. I would also suggest making the fake crab to experience the art of Chinese culinary abstraction. It is very much an impressionist‘s version of a dish of stir-fried crabmeat, perhaps even a cubist’s take on it given how jarring it is the first time one tastes it.

Not ready to re-enter the modern era? Here's how to speak English like a mid 19th Century Chinese merchant.

More stories by this author here.

Instagram: @gongbaobeijing

Twitter: @gongbaobeijing

Weibo: @宫保北京

Photos courtesy of Berkshire Publishing