OlymPicks: After the 2022 Games, Then What?

OlymPicks is an ongoing blog series wherein we highlight news, gossip, and developments regarding the buildup to Beijing's 2022 Winter Olympics.

Olympic Aftermath

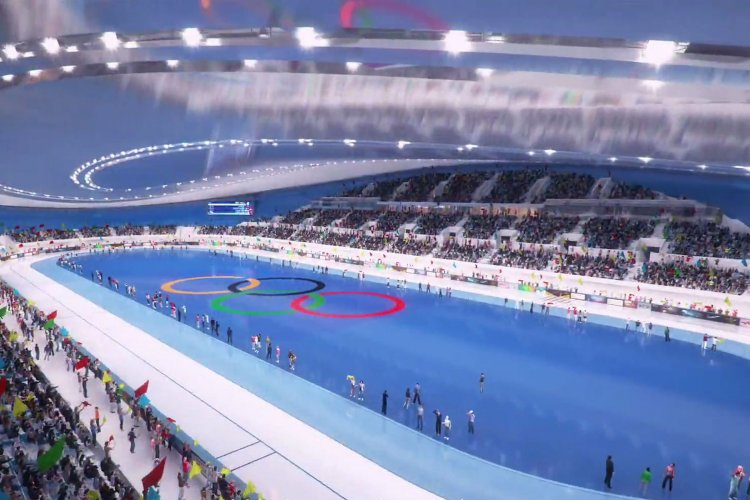

While hosting the Winter Olympics is no small feat, what comes after the closing ceremonies can be equally daunting. Beijing sports officials are currently under pressure to deliver a successful legacy plan for the Games in order to avoid wasting resources, make use of already established venues, and ensure that the event can offer benefits for years to come.

If they pull it off, they will be in rare company. In a recent article, Inside the Games explained that “legacy has been a major concern following last year's [PyeongChang] Winter Olympics and Paralympic Games, with doubts continuing to exist about the use of venues.” While South Korean officials certainly struggled with such issues after the hype died down in PyeongChang, a number of other host cities have also been criticized for building expensive venues that went on to dwindle in obscurity in the aftermath of the Games. The Travel even made a list of derelict sites, including the 2016 Rio golf course, the 2004 Athens softball field, and Beijing's 2008 BMX, kayaking, and volleyball venues (click the links to see the sites as they stand today).

As part of a more proactive approach, Beijing 2022 officials last week announced a detailed legacy framework. Key to its success: using existing venues rather than sinking too much money and resources into new development. The National Aquatics Center (better known as the Water Cube), will host curling events once its pool is outfitted with ice sheets. Hockey games will be held at the National Indoor Stadium (where gymnastics, trampolining, handball, and other competitions were held in 2008). Fittingly, the opening and closing ceremonies are set to take place at the Bird's Nest stadium.

Old Rails and New Dragons

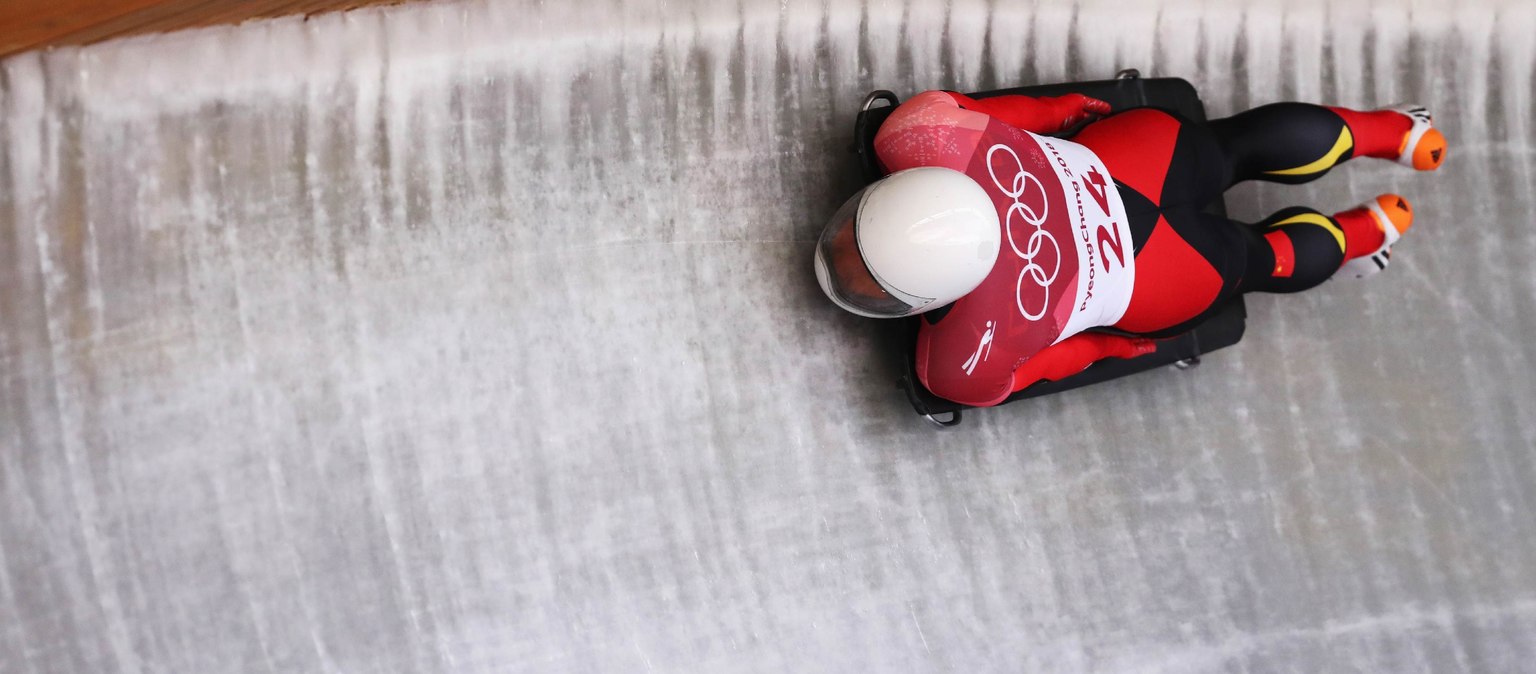

One of the less famous 2008 Olympic venues being repurposed for 2022 is the Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Stadium, which has been outfitted with rails to allow China's Olympic skeleton team to practice the crucial “running push” portion of their sport.

The team (a member of whom is pictured in the lead image above) will make use of those facilities until a new National Sliding Center opens on the Xiaohaituo mountain range (located in Yanqing, about 74km northwest of Beijing). Designed in the shape of dragon, its curvy track will “follow the mountain’s flanks, covering an area of 125,937sqm with a 127m vertical drop,” according to a recent olympic.org article.

Conservationists, in turn, will be happy to hear that the large facility already has a post-Games plan. "After the Beijing 2022 Games, the Sliding Center will become the training facility for the Chinese national teams, and will be looking to host international competitions," the article continues.

Among the skeleton team members now training at Shenyang, and poised to take advantage of the upcoming National Sliding Center, is Geng Wenqiang. The current team captain competed in the PyeongChang 2018 Games, where he finished 13th. “That was just the start,” he says of his performance at the last Winter Olympics in South Korea, making him one of many burgeoning athletes looking to score breakthrough wins for the home team in Beijing in 2022.

A Less Concrete Legacy

Another less concrete (pardon the pun) but crucial aspect of Beijing’s Winter Olympic legacy plan is training successful athletes who will inspire regular citizens to take up winter sports and thereby ensure that the facilities will be put to use down the line. That push was detailed in another recent olympic.org article about China’s ski jumping team, which says, "Every effort is being made to get them up to the highest possible level and, in the long term, create a real ski jumping culture in a country where winter sports are growing rapidly."

The article goes on to describe one of China’s top female ski jumpers: Chang Xinyue. While her background is in short track skating, she switched disciplines in the early 2010s and is now aiming to qualify, and then make a strong debut performance, at the 2022 Games. She is one of a handful of Chinese athletes who began training in earnest in Norway this past spring. Just like Chang, most of those hopefuls also transitioned to skiing after first making names for themselves in different sports. Despite that, Norwegian Ski Jumping Federation head Clas Brede Braathen is confident they have enough transferable skills to succeed on the slopes.

"Some of them have more than enough physical potential to become world number one; but before that, they need to do some ski jumping!" he told olympic.org, adding, "We believe in them. I am convinced that they can become Olympic athletes and, more importantly, that a ski jumping culture can be developed for people in China. That would be fantastic."

Work up a sweat with all our sports coverage, right here.

Photos: olympic.org, Burbex Brin, zimbio.com