In Conversation with Carolyn Phillips, Author of New Chinese Cookbook 'All Under Heaven'

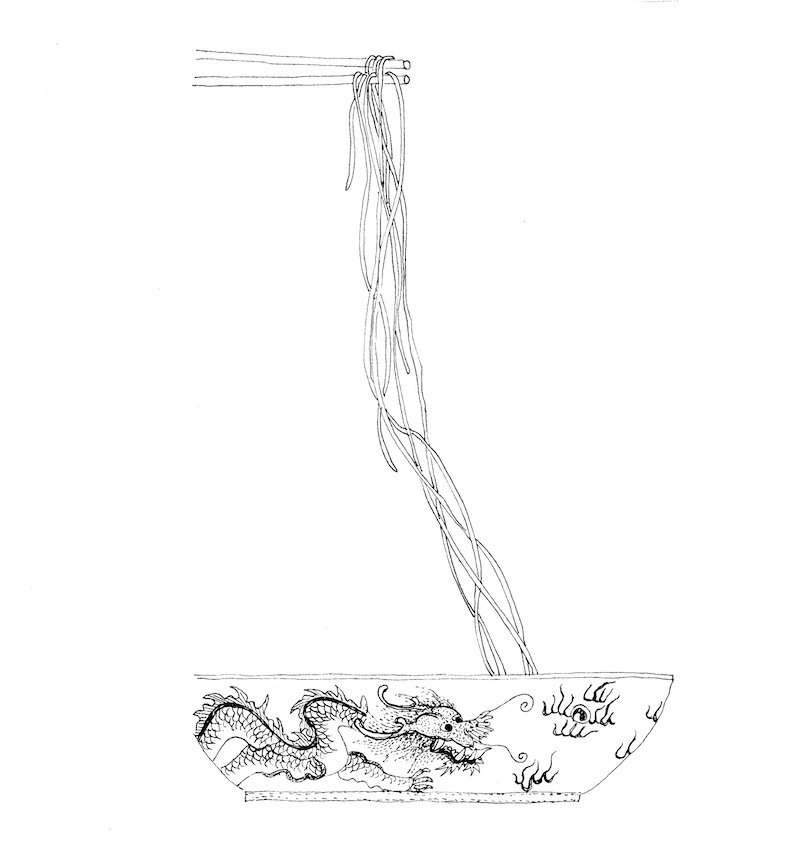

I have been following food writer, scholar, and illustrator Carolyn Phillips' excellent blog "Madame Huang's Kitchen" for years so it was with much excitement that I learnt that she was publishing a book, All Under Heaven: Recipes from the 35 Cuisines of China (McSweeney’s + Ten Speed Press, August 2016). A comprehensive look at China's many fascinating regional cuisines, All Under Heaven is as much a personal memoir and academic work as it is a cookbook – those looking for step-by-step recipes and plenty of pictures to flick through may want to look elsewhere (the book is instead illustrated with Phillips' own drawings). However, for a compulsive collector and reader of cookbooks, this is the perfect in-depth work.

Below, Phillips tells us about her culinary journey of discovery and offers some advice for budding food bloggers looking to make the leap from screen to page.

For those of us reading in Beijing, All Under Heaven is available for purchase as a Kindle book from Amazon.com or to order from The Bookworm.

What first brought you to Taiwan/China?

What I told my mom was that I wanted to learn Mandarin, but I think I just wanted to eat and eat. I had learned Mandarin and Japanese in college, and of course was therefore virtually unintelligible in either language. I applied to both Taipei and Tokyo for language classes, found a last minute opening in Taipei, and the rest is history.

How did you become so interested in Chinese cuisine?

My first two years in Taiwan in the late 70s had me dining on all sorts of street foods from every part of China, as well as great homecooked meals with my host family and lots of friends. My new Chinese husband then introduced me to an even broader variety of great cooking, and then when I worked as the main interpreter at the National History Museum and National Central Library for five years, this meant dining out many times a week at Taipei’s greatest restaurants. I really was in an amazing place at an amazing time, for many of China’s most renowned chefs had moved to Taiwan after 1949, and money started to flow into the island with the tech revolution, and so fabulous dining palaces were springing up all over with outstanding cooks at the helm.

As I ate my way across Taipei, I started to notice the differences between the many cuisines, and as I tried to get a handle on them, I started to read lots of books and even cook some of the foods I had eaten the previous week in an attempt to figure them out. I had always been told that there were eight great cuisines (Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, Hunan, and Sichuan), but the more I ate, the more confused I became, because this seemed to be such a limited view of what China had to offer.

When we returned to the States, I continued to try to parse my way through these food traditions, and although I worked as a Mandarin court interpreter during the day, in the evenings I spent more and more time working on this puzzle. I finally quit my day job to focus my attention on the cuisines of China and become serious about writing a cookbook. I started with my blog, and this gradually morphed into All Under Heaven.

What was the first Chinese dish that really spoke to you, one that stands out in your mind?

The first great meal of my life happened at a Cantonese restaurant when I was still in my preteens. My father had told me I could order whatever I wanted and have it to myself. I saw something on the menu called almond duck, and as I had never eaten duck before, this sounded particularly intriguing. It ended up being delicately seasoned and steamed meat that was boned and then formed into a patty, coated with water chestnut flour (I am analyzing this in hindsight, of course), and finally carpeted with sliced almonds before being fried. This luscious, crispy patty was chopped into squares and served alongside some sweet-sour plum sauce. I devoured the whole plate with a bowl of rice and a pot of tea, and my tender little mind was forever tweaked. Food never looked the same after that, and once I grew up, I knew I wanted to relive that experience of eating glorious meals on continuous repeat until the end of time.

How do you think Western perceptions of Chinese food have changed since you first moved to Taiwan?

Back when I first went to study in Taiwan four decades ago, we really only had Chinese-American food here in the States. A few exceptions like that almond duck episode aside, it wasn’t Cantonese per se, but more of a fusion cuisine. Sometimes it was great, but usually it was takeout egg foo yung and chow mein. Nevertheless, these dishes were still way more interesting than the Midwestern-style foods I was used to, and so I loved it.

Nowadays, of course, the more cosmopolitan areas of the US offer all sorts of regional Chinese cuisines, good dim sum teahouses, and well-stocked Chinese grocery stores. Much of this change over the past couple of decades is thanks to the many Chinese people who have moved to the States, the increasing number of vacations Americans have taken to China, a wonderful number of great television shows, and the countless folks who went to Asia to learn a language and came back – if not with a mastery of Chinese, then at least with a serious longing for great food. As a result, diners here are more sophisticated and many now know the difference between, say, Sichuan and Shanghainese cooking and are always on the lookout for great chefs and excellent Chinese restaurants.

What cuisine do you cook most at home? Has cooking Chinese cuisine influenced the way you prepare and cook Western dishes?

We usually eat something Chinese for dinner, not only because my husband is Chinese, but also because I’m almost always developing new recipes. He is my main guinea pig, of course.

That’s a great question about how Chinese techniques and ingredients work their way into my Western dishes. Soy sauce might deepen a gravy or stew in our home, or I’ll sneak Shaoxing rice wine into fish or chicken dishes, and I love the ways that rock sugar and Chinese-style caramelized sugar round out desserts. Toasted sesame or peanut oil rubs up against butter, green onions tend to be toasted in oil for another level of flavor for certain soups or braises, black mushrooms (xianggu) will lend their perfume to lots of savory dishes, and Chinese yams (shanyao) sometimes are subbed in for potatoes. Stir-fried vegetables seasoned with garlic and salt definitely are preferred in our house, and if I can slip in a little Chaozhou satay sauce or chili, so much the better.

Have you visited Beijing before? If so, what was your impression of the food?

Yes, I love Beijing! The people there are so lovely, and my favorite places to eat are the humbler restaurants on side streets and hutongs, where you get more mom 'n’ pop style foods. I’ve of course eaten in lots of the finer restaurants, but whenever I’m in Beijing, I really long to eat those traditional things you can’t get anywhere else, the ones made by people who create the same little masterpieces day in and day out. Some Chinese friends have also treated us to meals at Beijing’s fancier places, and we’ve eaten well there, too. But no matter where I go, I always seem to gravitate toward places that offer homestyle meals – simple but honest foods are my favorite.

You are also an illustrator; how does this influence your food writing and vice versa?

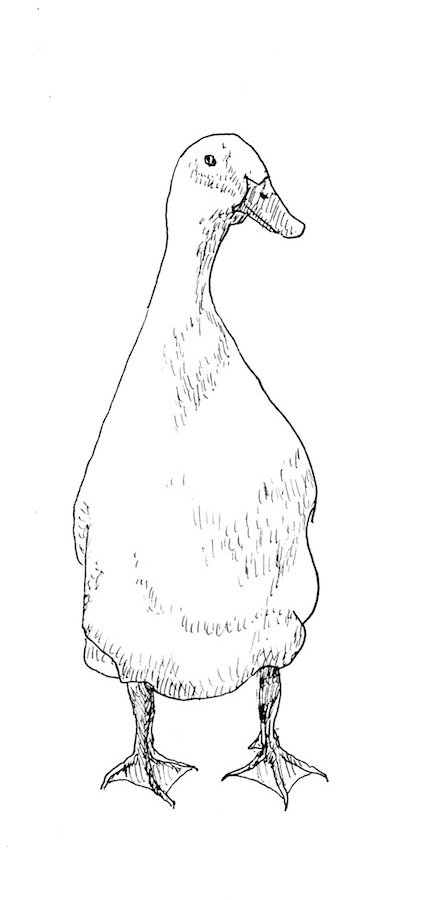

I like to illustrate my food writing whenever, and so it tends to go in the opposite direction: first I have the recipe and the story, and then I try to find a way to give it a visual spin. Sometimes it will highlight a particular ingredient – like a picture of a duck or a fish – or it might be the final dish or even something more evocative, like the Buddha for something vegan. Ideas will eventually pop into my head as I’m mulling over a recipe.

Which food writers have inspired and influenced your work?

Julia Child was the first, but over the years I’ve been entranced by so many wonderful writers. M.F.K. Fisher had a lovely way of dovetailing her life in France with the foods she was enjoying – her description of drying tangerine segments on the radiator to crisp up their skins against the juicy flesh remains intensely sensuous for me.

I adore Roy Andries de Groot’s Auberge of the Flowering Hearth, for it makes a lost age come alive, and I often wish I could somehow go back in time and tag along as he was wined and dined at that marvelous inn. Yuan Mei’s Suiyuan Shidan is cranky and funny and wonderful, the great Sichuanese chef Chen Jianmin has written some terrific cookbooks, and I also get a big kick out the tidbits that writers of literary sketchbooks (biji xiaoshuo) managed to insert into their books about the foods they ate and where they dined throughout the ages.

One of my all time favorite books is called Guxiang Zhi Shi (Hometown Foods) by Liu Zhenwei, since it has little vignettes about the many things he ate in China around the turn of the 20th century, back when tradition still held sway. It’s one of those rare, beautiful books that sunk its hooks into me a long time ago and is one that I return to for inspiration time and again.

What inspired you to make the leap from a blog to a published work?

The realization that I had a book in me took shape over many years. At the beginning, I just wanted to figure out some way to explain – at least to myself – the way that all of China’s cuisines fit together, what they were, why different places ate certain things, and how many food traditions there were. It was a labor of love! I learned so much from this, and of course, the more I asked, the more questions popped up. Things like the great influence of China’s Muslims on its cuisines gave me huge insights into the foods of China. And as I started to work out these puzzle pieces, I began to realize that this was in fact the making of a book and no longer just a pet project.

It took a long time to gestate, but All Under Heaven slowly morphed into its present shape thanks to many false starts and rewrites, as well as to the steady hands of a number of terrific editors at McSweeney’s and then at Ten Speed Press.

Do you have any advice for bloggers who are looking to get published?

First of all, if you are going to blog, be completely reliable. Figure out your schedule and stick to it. That is absolutely essential. Your readers have to be able to depend on you to come up with a new post whenever you say you will, and if you fail them, you’ve lost them.

Respond to your readers, too. If someone takes the time to not only read what I’ve written, but also to buy the ingredients and make these dishes, the very least I can do is answer their questions, right? And so I do. Getting feedback from my readers is so helpful, and I probably learn as much from them as they do from me. One of the most gratifying parts of this whole process is the stream of emails and tweets and notes I get from Chinese Americans (or other overseas Chinese) who have longed to cook the foods they ate as children, but who don’t read Chinese and so haven’t been able to connect with those recipes. When someone tells me that a dish tastes exactly like his or her memories, I’m over the moon with joy!

Second, be unique and specific. At first, my blog was all over the place – I have a couple of terrific recipes in there for things like dobos torte and English toffee pie, for example, that were part of that experimental phase – but later on I settled down to introducing the traditional foods of China from all over the country, along with stories and recipes that non-Chinese speakers could follow.

Third, create a good-looking website. There are all sorts of templates and web services out there, so find something you like and is easy to use. Then, figure out how to personalize it and make it user-friendly.

And finally, you have to be a regular Renaissance woman or man nowadays and take beautiful photos in addition to everything else. I’m still working on that part and so am particularly envious of anyone who effortlessly pulls off the photograph end of this business. Maybe that’s why I draw so much!

When it comes to writing a book, the only thing I can tell you is, don’t give up. Writing a book is really, really hard work, or at least it was for me. Part of the difficulty lies in finding your voice and in zeroing in on a subject that hasn’t already been covered to death. At the same time, this also has to be something that readers will want to actually buy. Locating the nexus where those two lines cross is very difficult, but it can be done if you have the time and the patience to suss it out. In the meantime, read and read and read as much as you can. You can never read too much. And eat as many different things as you can – that’s the fun part of the job.

Once you have the book written, don't expect people to fall all over themselves to publish your work. Something like that just doesn’t happen unless you are already famous. Believe me. What this means is that you ought to take the time write that book and rewrite it until it is as mature and flawless as possible. Get some writer friends to critique it for you, and then swallow your pride and carefully listen to what they have to say. (This part can be painful, but it can also be incredibly revelatory.) Then write your book once again.

Now we come to the part where you write a proposal. Dianne Jacob has a great book (Will Write for Food) and blog on doing just that. A proposal is what you will send an agent or publisher, not your book, so this is your one chance to make a great impression. That is why you need to work on it and make it shine. And if you can have someone read your proposal before you send it off, even better.

More stories by this author here.

Instagram: @gongbaobeijing

Twitter: @gongbaobeijing

Weibo: @宫保北京

Photos: epicurious.com, courtesy of Carolyn Phillips/Ten Speed Press, headshot: Karen Christensen, 2016