Advantage Almaty: Why Beijing's Olympic Legacy May Not Be a Plus

The Olympic inspection of Beijing is over, and for the next four months, we get to read tea leaves as to whether Kazakhstan's Almaty or Beijing will win the right to host the 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

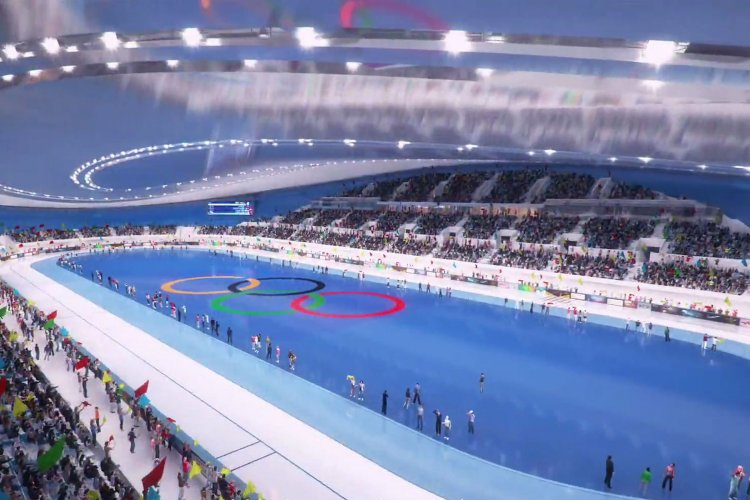

“From this visit we can see that your Games in 2008 have left a profound legacy," said Alexander Zhukov, chairman of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Evaluation Commission, according to a statement issued by the Beijing 2022 Committee. "We can see this legacy in the venues, and in your plans to use many of those venues in 2022."

But what about Beijing's Olympic legacy? How has our capital city fared since 2008?

Unlike some other recent Olympics hosts such as Seoul (1988), Barcelona (1992), and Sydney (2000), where the Games marked those places' entrance as world cities, Beijing 2008 marked the city's coming out party – but at the same time by some measures, it marked the beginning of years of decline for Beijing. Smog and traffic have gotten worse, foreign visitor arrivals have declined, and the city has seen an exodus of long-term foreign residents, and the cost of living has skyrocketed.

Play word association with anyone outside of China and the words you'll hear after "Beijing" will not be "Olympics," "Fuwa," "Water Cube" or "Michael Phelps Wins Eight Golds," but rather "PM2.5," "pollution," and "traffic."

And what of legacy Olympic venues?

Most of the stadia and arenas have been used only sporadically since their Summer Olympics heyday. The National Stadium (Bird's Nest) has seen only a handful of sporting events and concerts during the last seven years. The Water Cube did not become the country's best natatorium; instead, it has been converted into an indoor water park. The National Indoor Stadium, which was used for gymnastics events and team handball, has seen some action as a convention center in a city oversupplied with them. The Wukesong Stadium, since renamed the MasterCard Center, has been used for the occasional pop concert as well as matches from visiting NBA teams. Perhaps the National Tennis Center has fared best, not only hosting numerous daily players on its public course, but also the China Open, Beijing's best annual sporting event.

Maintaining these venues for a future Olympics bid makes Beijing's 2008 planning look good, but will Beijing bid for the 2036 Games, and reuse the same venues? What will become of these venues after 2022?

And exactly what sort of use will a brand new high-speed rail line to Zhangjiakou have after the Olympics, except for a few brief months each snowless winter?

Another part of that legacy is pollution, with which Beijing has become synonymous. Even on the final day of the Evaluation Commission's visit, AQI readings went beyond the index, although this was more a function of an early-season sandstorm than belching factories or too many cars.

"The Beijing smog feeds on itself. Whenever the city periodically disappears into a brownish-yellow haze, the traffic only gets worse. Those who are fortunate enough to own a car leave their bicycles at home, choosing air-conditioning over the unfiltered cocktail of coal smoke, particulate matter and ozone in the air." Sounds like yesterday? Like 2013? That paragraph appeared in Der Spiegel in 2007.

"I think, objectively, we can say that the Chinese authorities have done everything that is feasible and humanly possible to solve the situation or to address the situation." That statement was made on August 7, 2008, by Count Jacques Rogge, then the head of the IOC, the day before the Summer Olympics began. "The fog you see is based on humidity and heat," he explained. "Of course, we prefer clean skies but the most important thing is the health of the athletes being protected," Rogge said, at the same press conference.

Beijing had over five years to address pollution before it threw its hat in the Winter Olympic bidding ring. Instead of gradually addressing the issue, the situation has only worsened since the Olympics, including one of the first days when the index was exceeded.

The other problems are simple ones, although the IOC seems, at least outwardly, willing to gloss over them. Almaty gets snow, lots of it, and it's visible from the city center even in June. Beijing received barely a flake of snow during the winter of 2013-14, received more snow in the winter 2014-15, but still not a lot. When the Evaluation Commission visited Almaty, there was snow on the ground. When it visited Beijing, there wasn't. Think of it this way: for the Summer Olympics, visiting a location that's sunny and 26 degrees, now matter how you cut it, is more appealing as a host than somewhere that's overcast and 14 degrees. When you think of the Winter Olympics, you think of Innsbruck, not Indianapolis.

There are other issues. Does the IOC really want a Winter Olympics that can't be Facebooked, can't be tweeted, and can't be Instagrammed? Those applications were available in 2008, but are not now. Certainly, that could change before 2022, but then again, it may also not. Even if, as one official said, China doesn't need those sites, they are now part of much of the world's way of life. They will certainly be familiar to and often used by the many athletes that will visit Beijng to compete.

Lastly, it's worth remembering that before Beijing was a successful Olympic host city, it was also a failed bidder. In 1993, Beijing faced Sydney to host the 2000 Games. Sydney was the sure thing; Beijing was the future. As history reminds us, Sydney won that bid. What was significant then, and is significant now, is that most of the plans that were presented as part of the Beijing bid including an expansion of the Beijing subway system, were delayed by at least a decade as a result. The same thing could happen here if Beijing is not named as the host for 2022.

Beijing does big events well. One of the reasons that 2009-2014 was a period of decline was that, except for the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China, there were no big events during that time. Beijing hasn't had anything to look forward to since the October 1, 2009 celebrations ended. No Olympics; no bid for the World Cup; no significant political celebration or anniversary. What happens if we can't look forward to 2022?

We hope and want Beijing to win this bid. Heck, from the moment Beijing threw its hat in the ring, we've been predicting its success. So far, we've done pretty well: the field winnowed from six cities to two. The 2008 Olympics were great, and while the Winter Olympics are smaller and, well, held in the winter, they'll be fun to, and they'll be great for the city.

Right now Beijing looks like an overweight athlete that just held a press conference to announce a comeback. Almaty is a young whippersnapper that isn't quite ready for primetime. Almaty has nothing but a future; Beijing has a bit of a mixed history before and after the Olympics, and we hope the IOC won't hold that against us.

Photo: Beijing 2022 Media Office