Ecology: Diamond Mining in Pollution

In February, every Beijinger follows the same old, three-step routine. First: succumb to sputtering coughing fits. Second: mutter curses and pleas toward our smog clogged heavens. Then: begin the beleaguered process anew. But Daan Roosegarde envisions a refreshingly new breathing cycle for China's capital – one that practically leaves him panting because he smells so much potential in those polluted plumes.

The Dutch designer and head of Studio Roosegarde (a pair of art, fashion and architecture “social labs” based in the Netherlands and Shanghai) says one of Beijing's parks can be outfitted with devices that use simple static electricity to “scrub” 70-75 percent of the pollution in a 40-50 meter radius. He hasn’t decided on a specific park yet for the project. Roosegarde compares the proposal to a grander version of the air purifiers used in most European hospitals. But a more fitting analogy would include the famed "Beijing breathing bicycle" that made headlines last year, designed by British-born, Beijing-based artist Matt Hope.

Unlike the breathing bike, Roosegarde's plan would make use of pollution by compressing the smog’s carbon until those grubby particles turn to dazzling diamonds (which could, in turn, fund the process in other parks). But this high concept does share the same sentiment as Hope's more modest project. And like the diamonds he aims to pull literally out of thin (albeit filthy) air, Roosegarde's plan has a flaw that makes it all the more beautiful. Below, the Dutch designer and Lia van de Vorle – a bio-technologist he recruited to help bring the project to life – tell us about the deeper message behind the futuristic plan, the technical workings of its devices, and how the gunk in our lungs could become bling on our fingers.

How did you discover that smog could have benefits?

Daan Roosegarde: One day I was sitting in my hotel room in Beijing, looking out at the CCTV tower. By the next day the view was completely covered in smog. I thought it was incredibly sad.

But then I thought, rather than trying to reduce pollution, what if we could use it as a tool? My team has created a lot of environmental projects where we thought of sustainability as doing something more, rather than less. We’ve developed sustainable dance floors, which generate electricity as you dance on the floorboards and move them up and down. We also have a lot of experience with magnetic fields and static electricity. Right now we're building a new a road in Europe which charges electrical cars when they drive over it.

So I thought about static in simpler terms, like the way it electrifies balloons if they touch your hair. I thought the same thing could apply to smog.

How exactly will this work in the Beijing park?

Lia van de Vorle: The smog will be removed using the principle of positive ionization. Smog particles and polluted air will enter the device’s system. A high voltage electrode gives the particles a positive charge, which makes them move to a negative collector electrode. The smog particles settle on this collector electrode until they form harmless coarse dust. Then purified air leaves the system.

What will be the technical challenges?

LvdV: We had a successful pilot in the Netherlands, but the Beijing project’s systems will be bigger and the volume of air that needs to be purified will be much bigger. The greatest challenge that we still need to address is the fact that it will be a fully open space with various wind directions, which will affect the system’s configuration.

How much energy will it need to clean the air?

LvdV: We calculated that 240 cubic meters can be cleaned per hour with an energy consumption of 1500 watts. That’s comparable to the energy used in a standard oven or microwave.

DR: It’s quite energy efficient. The goal is to create a place that is at least 70-75 percent cleaner than the surrounding environment.

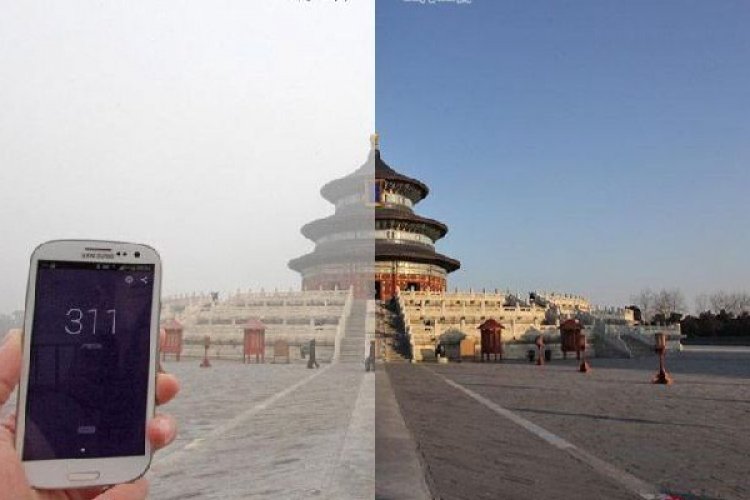

What would 70 percent less smog look like?

LVDV: This depends on the amount of smog. But as an example, Beijing’s average PM2.5 air quality is 250-270. If our system was operational, the air quality would be in the range of 75-80.

What about the process of turning smog to diamonds? How will that work?

DR: During our pilot project, I had some of the collected smog particles placed in a plastic bag. It was incredibly disgusting, and I thought, “My god, am I breathing this?” It was a lot of waste, which we could have thrown away. But our scientists started talking about how smog mostly consists of carbon. And what happens when you compress carbon? You get diamonds.

We're only in the testing phase now. Our plan is to compress some of the smog enough that it becomes a grey gel, then compress other parts until they become pure diamond. That way our jewelry will have colored layers, and you’ll be able to see bits in the diamond that used to be pollution. It’ll give it a really unique look. It’s doable – we’ve already made some, we're just fine-tuning to make it as energy efficient as possible. My girlfriend saw one, and now she keeps saying “I want a smog diamond!” So there’s no going back now.

For information about Studio Roosegarde's pollution scrubbing project, visit their website at Studioroosegarde.net.

For more articles like this, read the Beijinger magazine online:

Photos: courtesy Daan Roosegarde