Dave Eggers: A Heartpounding Talk with the Staggering Genius

In advance of his talk yesterday – which kicked off the first event in this year’s Bookworm International Literary Festival, Dave Eggers opens up about getting lost, visits to the Flying Pigeon Bicycle Factory, his narrative nonfiction writing process, balloon animals, and how publishing is most definitely not dying.

So when did you arrive in Beijing?

I have no idea. It’s a blur. I think it was just 2 days ago. I’m doing a little research while I’m here, and this morning was just able to be a tourist and go to the Forbidden City, then walk home and just get lost. It’s been great, and the weather reminds me of Chicago, so I feel very much at home.

Research?

Yeah I’m working on a book that has a few scenes that take place in China, so I did most of what I needed yesterday. I went to see the Flying Pigeon Bicycle Factory, so that kinda figures into the book a little bit, and then I’m gonna see some other factories while I’m here.

So what brings the book to China?

Oh, it’s too much detail, it’s too early to say. But I mean, … the Flying Pigeon Bicycle Factory is the closest I can get to explaining it. It’s too ephemeral right now, to, you know…

Bicycles are part of it. [Laughs.] I don’t mean to be evasive, I’m just in the middle of this book and it’s hard to talk about when I’m so deep in it. Don’t wanna jinx it.

And that whole drive to Tianjin, where all the factories are and all the bikes are made … It’s incredible because we drove for 2 hours and it was all industrial. Because everything looked, I mean it was hard to get your bearings. It was deadly serious out there. It looked like what we call the Rust Belt now, way back when, when it was just pure industry. It was exciting.

First impressions of Beijing?

It looks quite a lot like what I expected, having seen so much footage of it. But I always like to walk, you know, so I took a cab to the Forbidden City, and just got lost on the way back on purpose. And then when I reached a point where I had no idea where I was, that’s when it’s time to get in a cab. The funny thing was, if I had kept walking, I think I would have gotten home sooner, because you just sit there and um, you sit and wait. The traffic is insane. But I’ve been loving it. It’s pretty clear why there are so many Americans living here and why there are so many expats in general. And no one I talk to seems like they’re planning to leave. Nobody seems to have an expiration date, they’re all in love with it.

Back to your books: with What is the What and Zeitoun, you help other people tell their stories using a narrative nonfiction format. How did you go about doing that?

In both cases it was a mixture of interviews just like this, sitting side by side or across for hours at a time going over things, and then just asking, “And then what happened?” I mean that was my most common Q: “And then what? And then what? And then what?”

It was just perseverance and badgering I think. A good deal of the best material or the most telling moments or memories that become key happen when you’re just spending time together, walking around or eating a meal, or with Zeitoun it was just driving around sometimes going to his work sites which we always did. And things would occur to him that wouldn’t occur to him in an interview. And it also takes a long time to gain that level of trust where most of what he was telling me, he hadn’t even told [his wife] Kathy. You know in terms of what happened to him in prison and strip searches and all that stuff.

When you were approached with the first book, did you accept right away?

[With What is the What], I was really hesitant. I had no expertise in this. I had never been to Sudan, I didn't know any more than the average person about the war there. I hadn’t written a biography and I hadn’t thought of writing someone’s story like that.

I was naive because I thought it would take me a year to do it, and I promised him that it would be a year, and I was just a fool. It took four years. And the thing that drove it at that point was that you’re obligated to an actual person. If this were a book about Lincoln or something, I could have given it up and no one would have cared. But there was a guy waiting for the book on the other end. It was really difficult, that process, and knowing how many times I wanted to give up, and not having that option, was really hard.

And then when it was finally finished, I vowed never to do it again.

… Then I came across the Zeitoun story a few months after What is the What came out. And then I thought, "This story is incredible and no one knows it. And if I don’t write it it won’t be written." And then I again I was a fool. I thought, "This one for sure will only take a year to write. It’s domestic, and it just happened last year, and how long could it possibly take?"

But I’m an idiot when it comes to that stuff.

Maybe you’re just optimistic?

No it’s just pure foolishness. At least now I think I know how longs things take. To do things right, they take a long time.

So, narrative nonfiction or fiction, then?

Well, there’s one story I’ve committed to telling after this one. So, I mean I’m always attracted to non-fiction, and every week I see some story somewhere, or I hear some story and I think, that needs to be done! And I have to remind myself that …

... that there’s only one of you and way too many stories out there?

Exactly. There are too many stories that I think need to be told. But for the time being I’m really happy to not have to pick up a phone and ask, “What happens next?” But on the other hand there’s the disadvantage to not being able to pick up the phone and ask “What happens next?” You have to think of what happens next. So there are advantages both ways. But at least stylistically right now, working in fiction and not having to prove every word and number or date is really liberating.

It’s likely I’ll just keep vacillating between the two forms.

So what is it about a story that makes you just have to tell it?

Well I think you have to be attracted on a human level, on a lot of different levels actually. If Zeitoun’s story was just a man put in jail after Katrina, that might have intrigued me enough to write a book. But then you add on the fact that he’s Muslim American, and that gives it another facet. And then he’s a builder and a contractor from Syria. And that’s really interesting: the immigrant experience and the self-made man. These are all things that happen to resonate with me. I have cousins who are builders; I’m interested in that kind of life. And then you add his wife Kathy and her conversion, from an Evangelical home with 11 kids to converting to Islam, and then you add in all their kids who I got to know and I just instantly loved these kids, and I think it has to hit you on like 10 different levels. Because it’s just gonna be a hell of a lot of work, and it’s not a decision to be made lightly. Whatever this next thing or project is, it’ll almost kill me, so it better be worth it. And it would be very hard to put in three years into a book about … I don't know, balloon animals.

So, the McSweeney’s Quarterly … that’s another great place for you to get all those good stories out there, right? What’s your selection criteria like?

We’ll take anything that’s good. We’ll publish anything based on merit, no matter what form it’s in. It’s changed a lot, and will continue to change. It’s affected by what comes through the mail. If next month, it was ten amazing articles on balloon animals, we might put out a balloon animal issue.

Oh, so balloon animals aren’t worth three years of work, but maybe they're worth an issue of McSweeney’s?

[Laughs] Yeah, as long as I don’t have to write it. That’s the beauty of publishing stuff. It’s like bringing something into the world without having to carry it around for nine months.

I mean, it’s to have a vehicle. It’s just like at The Beijinger, it looks like people are having fun publishing – it’s very loose, the format of it, it reminds me of my first magazine Might in a way, where the headlines are fun and the captions are fun, and it looks like there’s this degree of inspiration and latitude there that is contagious when you read it. And I think that we’re trying to do the same thing, which is just be delighted by what comes through the mail. And be excited about opening envelopes and try to pass that on a little bit to the reader, the sense of discovery and surprise, you know.

Wow, that's very nice of you to say. (Readers: I promise I did not bribe him or feed him a cookie to say that. Honest.)

So, people are saying print is dead.

Well, we haven’t seen any death … I mean, we haven’t even seen any ill health where we are. In the numbers for the publishing industry as a whole, print was flat. It wasn’t going up and it wasn’t going down. When people say it’s dying, the data doesn’t bear that out. In a deep recession, when there’s a lot of competition from a lot of other media, book sales were still flat, so we can’t complain. DVD sales dropped precipitously and CD sales have dropped precipitously, but if you count e-books, book sales were up. So we’re feeling pretty good, we’re doing fine.

We think as long as you invest in the print form and make books something you want to own, and hold and keep, then they’ll survive. And that’s a specialty we have, to invest in the form of it, and making it something tactile, pleasing on a tactile level, something you won’t want to immediately recycle.

Every time there’s a new format whether it’s e-books or whatever it just means you have to do a little bit better, try a little harder, and that’s not bad. I think that anything that makes us do our best is probably a good thing. We’re eternally optimistic until we have reason to be otherwise.

There you have it folks. A statement from America’s literary darling that print is still alive and kicking. So go pick up one of his books, along with a copy of our February issue, which promises to be full of “inspiration and latitude.”

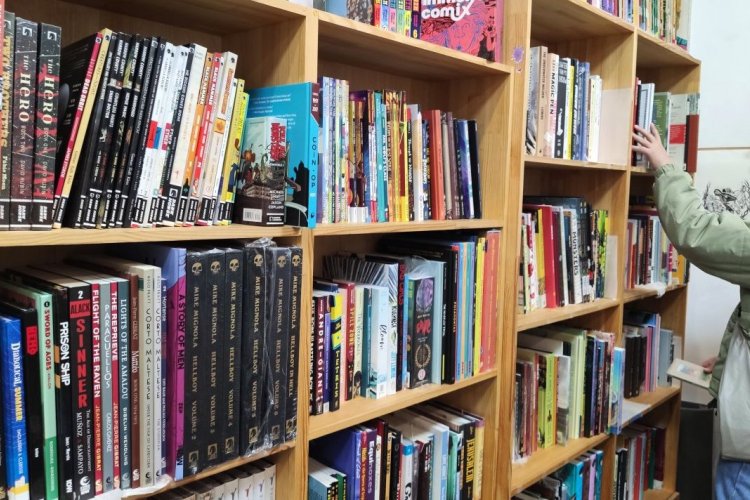

Dave Eggers' books are available at The Bookworm, as are volumes of McSweeney's Quarterly publication.

Also check out McSweeney’s online and, even cooler, 826 National, an organization co-founded by Eggers that helps set up tutoring centers for kids throughout America (and some in Europe). Best of all, the centers are run behind kick-ass storefronts like the Pirate Supply Store and The Museum of Unnatural History.