Story of the 'Jing: Legends and Myths of Jingshan Park

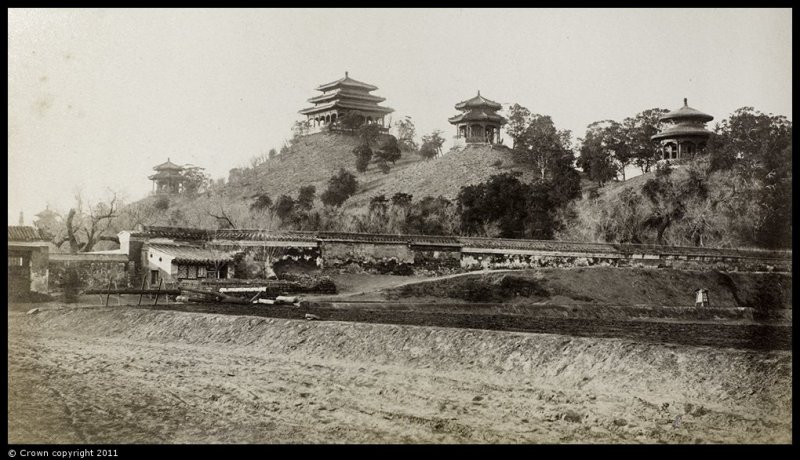

It might lack altitude, but at 45.7 meters (150 feet) Jingshan is the tallest point of land inside the Second Ring Road. Sitting astride Beijing’s famous Central Axis, the artificial hill also represents the geographic point zero for the historic capital of the Ming and Qing Emperors. On a good day, the top offers 360-degree views and is a popular place to watch the sunset behind the Western Hills.

As befits a landmark that sits at the very heart of old Beijing, there are numerous legends and stories about Jingshan and the surrounding garden.

There’s coal in them thar hills

The name of the hill has changed a lot over the years. It was called Qīngshān 青山 or Zhènshān 镇山 in the era of Mongolian rule (1276-1368) and Wansui Shan (万岁山 “Longevity Hill”) during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Since the “longevity” of Ming Dynastic rule wasn’t a top concern for the Qing rulers who replaced the Ming in 1644, the Qing court renamed the hill Jingshan 景山, usually translated as “Prospect Hill,” although “Lookout Hill” or “That Hill with the Super Awesome Views” would also work.

Some old foreign maps of Beijing labeled Jingshan as “Coal Hill,” which seems an odd choice for an imperial garden setting. Why Coal Hill? Two theories exist. Colloquially, the hill was also known as Beautiful Hill (美山 Měishān). One theory is that people mistook that name for Měishān 煤山 "Coal Hill." (Fun! With! Tones!).

However, there is a persistent legend, possibly true, that in the earliest days of the Ming Dynasty, coal and other supplies were stored at the base of the hill in case those pesky Mongolians besieged the city. While it is not the case that the interior of the hill is made up of coal, over the years park authorities have had to stop a few people from digging their own DIY coal mines in the side of the hill.

The hill is filled with the debris left over when the Forbidden City was built.

Some of the rubble from the destruction of the old palace of Kublai Khan and the debris left over when the Ming court built the Forbidden City was used as filler for shaping the hill and giving Jingshan its distinctive five peaks, but the Ming-era engineers were following a precedent set in earlier eras.

The Liao (916-1125) and Jin Empires (1115-1234) also had capitals on the site of present-day Beijing. The earth and stones their builders removed while expanding an earlier version of Beihai Park were then used as the original foundation for what would become Jingshan. Under the Mongolians and then the Ming, the hill took on a greater significance as a barrier protecting the palace from baleful northern spirits. In the Ming and Qing era, Jingshan also balanced the “Golden River” flowing in the front of the Forbidden City, helping to preserve the feng shui of the imperial residence.

The Emperor hanged himself from a tree in the park.

That’s the story. The Chongzhen Emperor [r. 1627-1644], the last ruler of the Ming Dynasty in Beijing committed suicide after the armies of the rebel Li Zicheng had breached the gates of the capital and taken control of the city. Accounts vary as to exactly where he did this and what happened to his body.

The Qing armies, who arrived in the name of “keeping the peace,” reportedly sought to placate Ming loyalists by punishing the offending tree used by the emperor. A heavy iron chain was tied around its trunk and it was renamed the “Guilty Tree” (罪槐 Zuìhuái). (Another account has the emperor ironically using the rafters of the Pavilion of Imperial Longevity). In the 1930s, the recently opened Palace Museum — perhaps thinking of adding an attraction — placed a stone tablet marking the spot of the “Guilty Tree.” Whether the current occupant of the location is the actual tree is unlikely. Park records suggest that replacement trees have been moved to the spot over the years to keep up appearances.

Jingshan was a not-so-secret military base

The proximity of the hill to the Forbidden City, its height relative to the rest of the city, and its central location have at times made Jingshan a strategically important position.

Emperors and their officials would often climb the hill to get a better vantage point on defenses and in cases of fire in the city. In 1900, foreign soldiers in Beijing, part of the Allied Expeditionary Force against the Boxers, occupied the hill (although that was as much about looting the imperial halls, shrines, and temples of their artifacts as tactics). When the warlord Feng Yuxiang decided in 1924 that it was time to boot Puyi, the last emperor, from the Forbidden City, he sweetened the deal by telling the young former monarch that Feng’s troops had set up cannons on Jingshan aimed at Puyi’s location in the Forbidden City. The last emperor got the point and moved out.

Finally, while the hill became a public park in 1928, the Chinese government closed it again between 1950 and 1955 when the top of Jingshan was used as an air defense position by the People’s Liberation Army.

About the Author

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, organizing history education programs and walking tours of the city, including deeper dives into the route and sites described here.

READ: Story of the 'Jing: What's Behind the Name "Summer Palace"?

Images: Zhang Kaiyi (Unsplash), University of Bristol, Wikicommons, Jeremiah Jenne